New findings from researchers at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) demonstrate that a mutation in one of the genes coding for human leukocyte antigen (HLA) may explain why some people exposed to COVID-19 don’t become sick. The mutation appears to allow T cells to identify the virus very early after infection, even if they have never encountered it before, due to its resemblance to seasonal cold viruses the immune system already recognizes. This discovery highlights potential new targets for both drugs and vaccines to fight the virus.

“If you have an army that’s able to recognize the enemy early, that’s a huge advantage,” said Jill Hollenbach, PhD, professor of neurology, as well as epidemiology and biostatistics at UCSF and the lead author of the study. “It’s like having soldiers that are prepared for battle and already know what to look for, and that these are the bad guys.”

The mutation called HLA-B*15:01 was carried by about 10% of the people in the study and while it doesn’t prevent infection by the virus, it does prevent people from showing any symptoms. The investigators found that 20% of the people who were asymptomatic after infection carried at least one copy of the HLA-B*15:01 variant, while 9% who reported symptoms carried the variant. Further, people with two copies of the variant were eight times more likely to escape having any symptoms.

For their research, the UCSF investigators tapped the National Marrow Donor Program/Be The Match, the largest registry of HLA-typed volunteer donors in the U.S., that was built to match donors with people in need of bone marrow transplants.

The investigators recruited roughly 30,000 people who were in the registry and followed them for the first year of the pandemic, a time when no vaccines were yet available and many people were undergoing routine COVID testing in their workplaces, or whenever they might have been exposed to the virus.

From this group, the investigators found 1,428 people who tested positive for the virus between February 2020 through April 2021, before the vaccines were available and testing often took many days to deliver results. Of the group who tested positive, 136 remained asymptomatic for at least two weeks before and after the testing positive.

In two independent cohorts, the UCSF team showed that only one of the HLA-B*15:01 HLA variants was strongly associated with asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection. Known risk factors for severe infection such as obesity or having a chronic disease did not play a role in those who remained without symptoms.

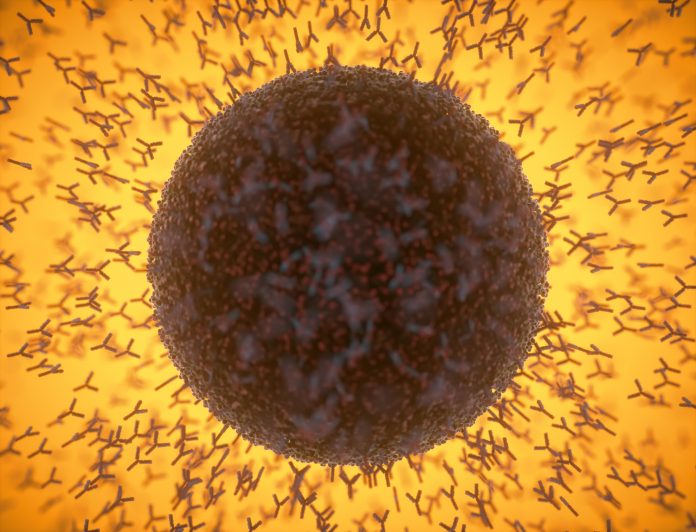

Once HLA-B*15:01 was identified, the researchers, including those from La Trobe University in Australia, focused on the concept of T-cell memory—the mechanism by which the immune system “remembers” past infections.

Studying people with HLA-B15 who had never been exposed to the virus, the team found that their T cells responded to a piece of SARS-CoV-2 called the NQK-Q8 peptide and concluded that exposure to other seasonal coronaviruses that have a very similar peptide, NQK-A8, enabled fast recognition of the novel coronavirus to create a fast, more effective immune response.

“By studying their immune response, this might enable us to identify new ways of promoting immune protection against SARS-CoV-2 that could be used in future development of vaccine or drugs,” noted Stephanie Gras, a professor and laboratory head at La Trobe University.