Therapeutics targeting RNA splicing can activate antiviral immune pathways in triple negative breast cancers (TNBC) and trigger tumor cell death, according to a study just published by researchers at Baylor College of Medicine. The study shows that endogenous mis-spliced RNA in tumor cells mimics an RNA virus, leading tumor cells to self-destruct as if fighting an infection. Researchers suggest this mechanism could open new avenues for activating the immune system in aggressive cancers like TNBC. It may also point to a means of determining which tumors are most likely to respond to immunotherapies.

The co-lead author of the study, which appears in Cell, is Elizabeth A. Bowling.

“Our study highlights an unanticipated way to activate an inflammatory response through specifically targeting cancer cells. These findings emphasize that when we think about the activity of cancer therapeutics, we need to look both at how they impact cancer cells as well as the effect this might have on the immune system,” said Bowling.

About 10-20% of breast cancers are triple negative, meaning they are negative for both estrogen and progesterone receptors as well as excess HER2 protein. As a result, TNBC does not respond to many common treatments for breast cancer. There is high interest in developing better treatments for these tumors. Immunotherapies, in particular, can be very effective, but so far they only work in a relatively small percent of patients.

“We know therapeutics that partially interfere with RNA splicing can have a very strong impact on tumor growth and progression, but the mechanisms of tumor killing are largely unknown. In this study, we discovered that these therapeutics are modulators of anti-tumor immunity,” said Trey Westbrook, PhD, corresponding author of the study and executive director of the Therapeutic Innovation Center (THINC).

RNA splicing–the removal of non-coding introns–is often deregulated in tumors, leading to tumor growth but also making the tumor hypersensitive to spliceosome-targeted therapies (STTs). Triple negative breast cancer is one of many aggressive cancers that are responsive to STTs.

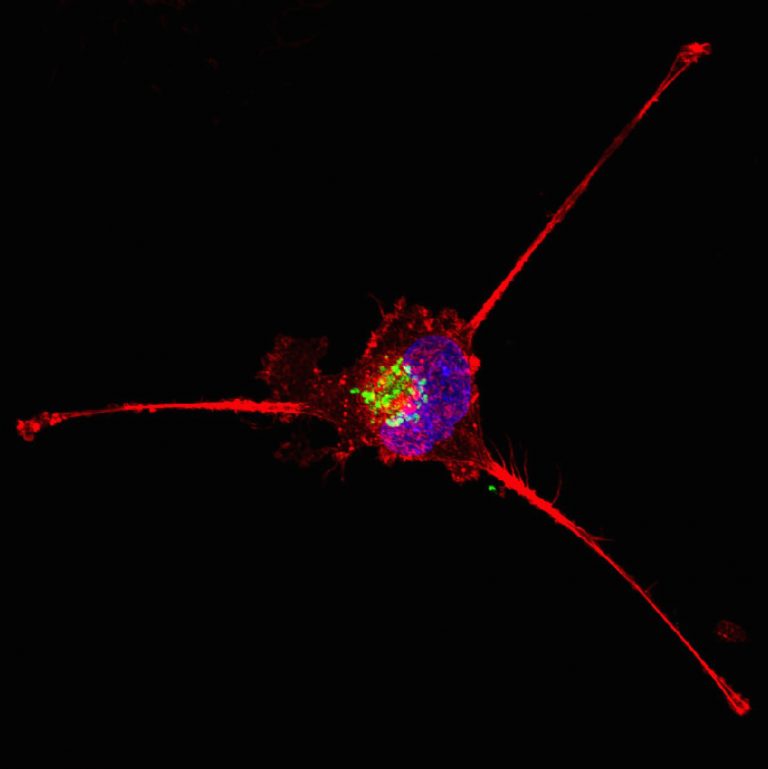

Westbrook’s team wanted to understand how those drugs interfere with tumor progression. They found that in TNBC cells, STTs interfere with RNA splicing and cause a buildup of endogenous mis-spliced intron RNA in the tumor cell cytoplasm. Many of those aberrant RNAs will form double-stranded structures, just like an RNA virus. Antiviral immune pathways recognize the double-stranded RNA and then trigger apoptosis and send signals to the body’s immune system to illicit an inflammatory response.

“We now have a clearer understanding of how high levels of mis-splicing results in cellular stress in breast cancer. Furthermore, we suspect this RNA splicing stress may be present in many cancer types and disease states,” said Jarey Wang, co-first author of the paper.

The authors point out that these discoveries may also lead to new biomarkers to select patients that respond to current immune-modulating therapies. Their work suggests that a tumor cell’s endogenous mis-spliced RNA may be able to stimulate the immune system even without using SSTs. The data shows a correlation between mis-spliced RNA and immune signatures, even in tumors that are typically immune-cold, and so do not have high levels of T cells. The study authors hypothesize that this endogenous mis-spliced RNA could be used as a clinical biomarker to find which cancers will be sensitive to immunotherapy. The researchers say further study is needed to determine if STTs activation of anti-tumor immune pathways could make more patients eligible for immunotherapy.

“While immunotherapy is having profound effects for some cancer patients, it still only works in a minority of cancer patients. It’s imperative that we learn how to broaden the swath of patients who might benefit from immunotherapy. This discovery uncovers a new mechanism by which cancers are speaking to the immune system and gives us strategies to exploit that for the benefit of patients,” said Westbrook.