Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis is launching an international clinical trial aimed at preventing Alzheimer’s disease in younger people at risk of the disease based on their genetics. Unlike most other Alzheimer’s prevention trials, this one will enroll people before the disease has taken hold—up to 25 years before the expected onset of dementia, which typically occurs in the 60s, but can happen much earlier.

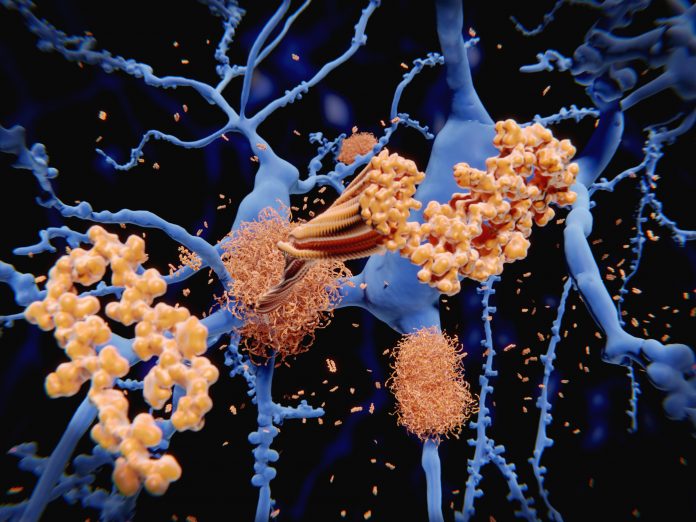

The team are studying about 230 participants from families that carry genetic mutations that lead to early-onset Alzheimer’s disease. The participants come from sites on five continents and have no or very few amyloid deposits. The trial will test the investigational drug gantenerumab over four years, with a goal of determining whether early treatment will prevent the buildup of the toxic protein.

“This trial is the first of its kind in that it aims to intervene before the onset of significant neuropathology in those young adults who are at a very high risk of developing the debilitating symptoms of Alzheimer’s dementia,” said Laurie Ryan, PhD, chief of the Clinical Interventions and Diagnostics Branch in NIA’s Division of Neuroscience. “We now know that changes in the brain can begin a decade or more before symptoms appear, so this trial is designed to provide another piece in the Alzheimer’s prevention puzzle.”

Called the Primary Prevention Trial, the new study will test whether gantenerumab can clear amyloid beta and slow or stop the disease. Gantenerumab is under development for Alzheimer’s disease by Roche and Genentech, a member of the Roche Group.

“Overwhelming evidence suggests that the most effective way to slow or stop amyloid beta is to prevent it from building up in the first place, but most of the drugs targeted to this protein have been tested in people who already have at least some early signs of the disease, such as memory loss – when the disease is far enough along that reducing amyloid alone isn’t likely to stop it,” said Eric McDade, DO, an associate professor of neurology and the trial’s principal investigator.

“We’ll be recruiting participants as young as 18. In many ways, this trial will be a necessary test of the amyloid hypothesis, which has had a major influence on Alzheimer’s research and drug development over the past 30 years,” he added.

The new trial involves families with rare genetic mutations that cause Alzheimer’s at a young age—typically in a person’s 50s, 40s or even 30s. A parent with such a mutation has a 50% chance of passing it to a child, and any child who inherits the mutation is all but guaranteed to develop symptoms of dementia near the same age as his or her parent.

Forestalling the earliest signs of disease could be game changing in the world of Alzheimer’s prevention, and the study has garnered support from all quarters: a U.S. governmental agency, nonprofit organizations, individual benefactors, and the health-care company Roche and Genentech. More than $130 million has been earmarked for the trial, including grants totaling an estimated $97.4 million from the National Institute on Aging (NIA) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), $14 million from the Alzheimer’s Association and the GHR Foundation, and up to $11.5 million from longtime Washington University benefactor Joanne Knight of St. Louis and family.

“This trial is the first of its kind in that it aims to intervene before the onset of significant neuropathology in those young adults who are at a very high risk of developing the debilitating symptoms of Alzheimer’s dementia,” said Laurie Ryan, Ph.D., chief of the Clinical Interventions and Diagnostics Branch in NIA’s Division of Neuroscience.