Researchers from the University of Virginia School of Medicine have learned that germline mutations, or inherited gene variations, are associated with cancer prognosis during and after treatment. Using genetic data from cancer patients, the team showed that each single genetic factor, as well as tumor grade, stage, and type, along with patient age, improved the prognostic predictive ability by 5% to 10%.

So why exactly do patients with the same tumor, grade, stage and treatment have different outcomes? “The assumption has always been that there is something that we didn’t understand, like maybe there are some tumor-specific mutations that one patient had but the other did not,” the authors say.

The researchers did know, however, that germline variants can predict a patient’s risk for developing cancer. They can also affect drug sensitivity, predict drug toxicity, and could help select therapy to minimize side-effects. And some germline variants increase patient risk for specific somatic aberrations, suggesting that germline variation may impact disease course. From this, the researchers set out to study the effects of germline variants on cancer progression to see if they may be strong enough to identify associations with patient outcome.

Armed with this hypothesis, they studied genomic data in The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) looking for a way to correlate inherited genetic variations with patient outcomes.

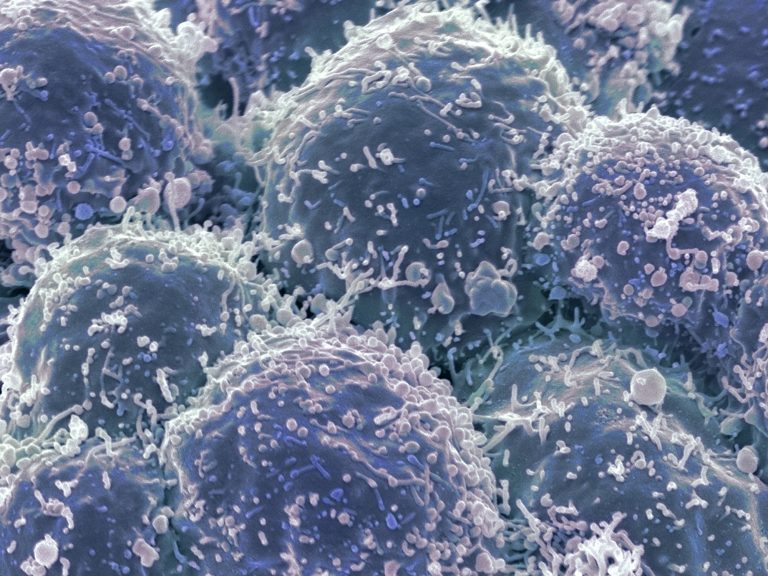

Studying 33 different cancers in the TCGA, which includes genomic data of 10,000 individuals, they identified several germline variants—not just tumor-specific mutations—that were inherited from the parents and are present in all cells of the patient.

The team next studied clinical outcome data for each patient using the TCGA Pan-Cancer clinical data resource and found that several cancer types had multiple inherited genetic changes associated with prognosis. Together, each factor combined in an additive manner increasing the team’s ability to predict how patients would respond to treatment.

Specifically, they identified 79 prognostic germline variants in individual cancers and 112 prognostic germline variants in groups of cancers. Molecularly, at least 12 of the germline variants were found to likely be associated with patient outcome and are known to have roles in substantial changes to protein structure.

Almost half of the germline variants were in previously reported tumor suppressors, oncogenes or cancer driver genes, including MSH6, POLQ, ARID5B, and IDH2, with the other half pointing to genomic loci that the authors believe should be further investigated for their roles in cancers.

About 25% of the predictive genes were previously studied in the cancer in which the germline variant was found to be prognostic, about half were previously studied in at least one cancer, and roughly two thirds were studied in at least one human disease.

The hope is that by reviewing the inherited germline variants of a particular patient, one can more accurately predict outcomes and choose the most appropriate treatment for cancers as well as other diseases.