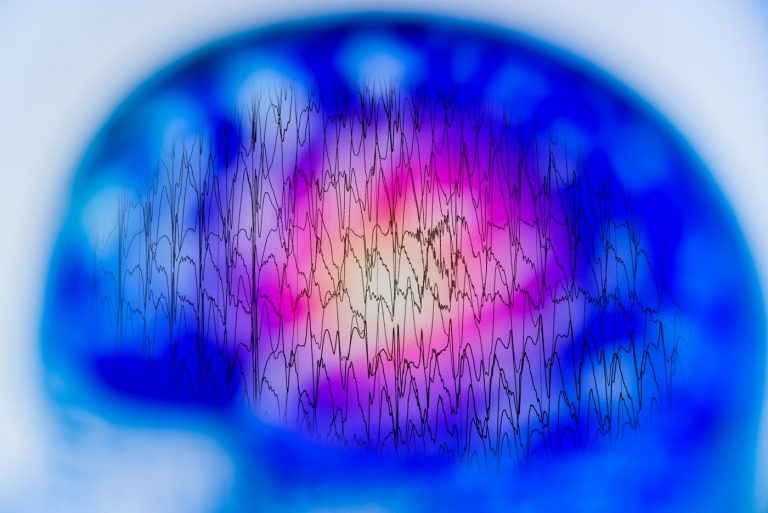

An analysis of electronic medical records data, carried out by researchers at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, links symptoms of childhood epilepsy at certain ages with variation in specific genes.

The researchers hope the information they collected will help clinicians give families more information about how their child’s epilepsy might progress over time based on their genetic profile.

The team found significant links between having ‘status epilepticus’ seizures – seizures of 5 minutes or more, or two or more linked seizures – and variants in the gene SCN1A at 1 year of age. They also found links between severe intellectual disability and variants in the gene PURA at 9-10 years, although this was only in a small number of individuals, and between variants in the gene STXBP1 and infantile and epileptic spasms at the age of 6 months.

“Our study is the first example in childhood neurological orders to systematically connect genomic information with the medical records,” says Ingo Helbig, MD, a physician at the Children’s Hospital and researcher at the University of Pennsylvania, who led the study.

“This is really important as we need to understand the clinical features that children with genetic brain disorders, especially children with genetic epilepsies, develop over time. Using the technologies that we have developed, we can use the available data in the electronic medical records to bridge the gap between genetics and outcomes.”

There are known to be more than 200 genetic causes of epilepsy, but information about long-term phenotypes linked to these causal genetic variants is less clear. While genomic information on patients is now fairly standardized, the collection of phenotypic data on symptoms over time has been less organized.

In recent years, electronic medical records have made large-scale analysis of symptom data a more manageable task. For this study, which was published in the journal Genetics in Medicine, Helbig and colleagues analyzed physician input of diagnoses made at 62,104 patient visits for 658 individuals who either had known or suspected genetic epilepsy.

To standardize symptom descriptions, the researchers used 286,085 terms from the Human Phenotype Ontology database to describe individual diagnoses. Overall, 102 distinct genotypes were found in the study group, with 36 causative genes. The team assessed gene and phenotype associations over 3-month time intervals ranging from 0 to 25 years of age.

Notably, the researchers found that the information they collected about how phenotypic features of epilepsy sub-types develop over time did largely reflect the timings described in the medical literature.

“With new precision therapies emerging, there is a pressing demand to understand the natural history of rare genetic epilepsies,” said Sudha Kessler, MD, a neurologist based at the same hospital who was not an author on the study.

“Electronic medical records are an untapped resource to learn about how very rare disorders present over time, which will allow us to include this information in our clinical practice.”

The researchers acknowledge that their study could have been subject to bias as different physicians may have described symptoms differently. They also note that they only looked at patients from one healthcare system. However, they believe this is just the first step towards larger and more in-depth analyses of electronic record data, which will significantly benefit patients and their families in the future.