A new study has linked a set of proteins in non-neuronal brain tissue involved in glucose metabolism with the development of Alzheimer’s disease (AD). This new information could shed light on the development and causation of the debilitating disease.

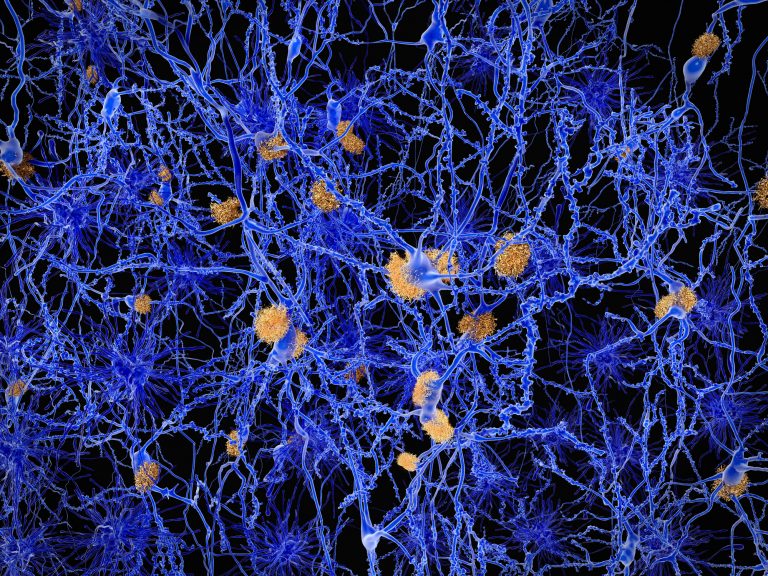

In the largest proteomic study to date in Alzheimer’s disease, a team of researchers has identified disease-specific proteins and biological processes that could serve as new treatment targets and/or patient biomarkers. The results of the study suggest that proteins known to regulate glucose metabolism, along with proteins associated with the protective role of astrocytes and microglia—brain cells that support and protect neuronal cells in the brain—are strongly associated with Alzheimer’s pathology and cognitive impairment in diseased patients’ brains.

The study, part of the Accelerating Medicines Partnership for Alzheimer’s Disease (AMP-AD), measured the levels and expression patterns of more than 3,000 proteins found in brain tissue and cerebrospinal fluid samples collected from multiple research centers across the US. This research was funded by the National Institutes of Health’s National Institute on Aging (NIA) and published April 13 in Nature Medicine.

“This is an example of how the collaborative, open science platform of AMP-AD is creating a pipeline of discovery for new approaches to diagnosis, treatment and prevention of Alzheimer’s disease,” said NIA Director Richard J. Hodes, M.D., in a press release. “This study exemplifies how research can be accelerated when multiple research groups share their biological samples and data resources.”

The research team, led by Erik C.B. Johnson, M.D., Ph.D, Nicholas T. Seyfried, Ph.D., and Allan Levey, M.D., Ph.D., all at the Emory School of Medicine, Atlanta, analyzed protein expression patterns from more than 2,000 individual human brain and nearly 400 cerebrospinal fluid samples from both healthy people and those with AD. The paper’s authors, which included Madhav Thambisetty, M.D., Ph.D., investigator and chief of the Clinical and Translational Neuroscience Section in the NIA’s Laboratory of Behavioral Neuroscience, identified protein interactions that reflect biological processes in the brain.

The researchers then analyzed and compared how the protein modules related to various pathologic and clinical features of Alzheimer’s and other neurodegenerative disorders. They saw differences in groups related to glucose metabolism and an anti-inflammatory response in glial cells from brain samples from both people with Alzheimer’s as well as in samples from individuals with documented brain pathology who were cognitively normal at time of death. This suggests, the researchers noted, that the anti-inflammatory processes designed to protect nerve cells may have been activated in response to the disease.

The researchers also attempted to reproduce these findings using cerebrospinal fluid samples, in order to determine if these protein complexes could serve as a future biomarker in living patients since brain tissue cannot normally be sampled in living patients. The team found that, similar to brain tissue, the proteins involved in glucose metabolism are also increased in the spinal fluid in people with AD. Many of these same proteins were also elevated in people with preclinical Alzheimer’s, or individuals with brain pathology but lacking the typical disease phenotype of cognitive decline. Interestingly, the glucose metabolism/glial protein complex was populated with proteins known to be genetic risk factors for AD, suggesting that the biological processes reflected by these protein families are involved in the actual disease process.

“We’ve been studying the possible links between abnormalities in the way the brain metabolizes glucose and Alzheimer’s-related changes for a while now,” Thambisetty said. “The latest analysis suggests that these proteins may also have potential as fluid biomarkers to detect the presence of early disease.”

Thambisetty and colleagues, in collaboration with researchers at Emory, found in a previous study a connection between abnormalities in how the brain breaks down glucose and the amount of the signature amyloid plaques and tangles in the brain, as well as the onset of patient symptoms such as memory problems.

“This large, comparative proteomic study points to massive changes across many biological processes in Alzheimer’s and offers new insights into the role of brain energy metabolism and neuroinflammation in the disease process,” said Suzana Petanceska, Ph.D., program director at NIA overseeing the AMP-AD Target Discovery Program. “The data and analyses from this study has already been made available to the research community and can be used as a rich source of new targets for the treatment and prevention of Alzheimer’s or serve as the foundation for developing fluid biomarkers.”

The brain tissue samples used in this study came from autopsies of participants in Alzheimer’s disease research centers and several epidemiological studies across the country, including the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging (BLSA), Religious Orders Study (ROS) and Memory and Aging Project (MAP), and Adult Changes in Thought (ACT) initiatives. The brain collections also contained samples from individuals with six other neurodegenerative disorders as well as samples representing normal aging, which enabled the discovery of molecular signatures specific for Alzheimer’s. Cerebrospinal fluid samples were collected from study participants at the Emory Goizueta Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center. These and other datasets are available to the research community through the AD Knowledge Portal, the data repository for the AMP-AD Target Discovery Program, and other NIA supported team-science projects operating under open science principles.