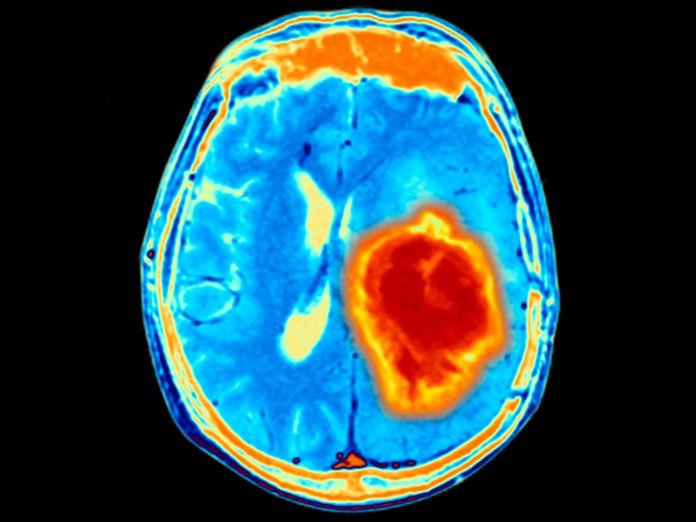

Results from a Phase II clinical trial show immunotherapy with pembrolizumab provided a benefit in 42 percent of patients with brain cancer that metastasized from a range of primary tumors. This study was designed as an open-label, single-stage, single-arm Phase II clinical trial evaluating the intracranial efficacy of pembrolizumab, a PD-1 inhibitor, in patients with brain metastases from 14 different primary cancers. The results were published in Nature Medicine and presented at the 2023 ASCO Annual Meeting.

The trial included 57 patients, most (35) with a history of breast cancer. Nine patients had previously untreated, asymptomatic brain metastases; the remaining 48 patients had recurrent and progressive disease after prior therapy.

“This study is the first histology-agnostic trial dedicated specifically for the brain metastases population evaluating intracranial efficacy of pembrolizumab,” the authors wrote.

The research team found that 24 of the 57 patients had an intracranial benefit defined by complete response, partial response, or stable disease. Seven patients in the study experienced prolonged overall survival of two or more years, including five patients with primary breast cancer, one patient with primary melanoma, and one patient with primary sarcoma.

Toxicity was a concern as nearly half of treated patients had one or more grade-3 or higher adverse events likely related to pembrolizumab. Grade 4 toxicity involving cerebral edema was observed in two patients. A total of 13 patients discontinued treatment for adverse events, the most common including fatigue, nausea, headache, vomiting and transaminitis (elevated levels of liver enzymes in the blood). The authors found that toxicity exceeded those seen in other clinical studies evaluating PD-1-related monotherapy.

This study joins the growing list of clinical studies showing the benefit of immunotherapy in brain metastases from melanoma and non-small lung cancer. However, investigations of immunotherapy for brain metastases originating from other sites in prospective clinical trials have been limited. The authors believe these findings combined with the efficacy observed in non-cranial cancers, provide additional evidence that immunotherapy deserves further investigation as first-line treatment for brain metastases.

“Our work suggests that the decision to give a checkpoint inhibitor should not be based solely on the primary tumor’s origin—it is likely that there are yet-to-be determined factors that may predict response,” says corresponding author Priscilla K. Brastianos, MD, of the Massachusetts General Hospital Cancer Center. “Future studies to identify these factors may help guide, inform, and personalize treatment for patients with brain metastases.”

As next steps, the research team recommends investigating biomarkers of response, especially among the study’s “exceptional responders,” that may help to predict which patients are most likely to respond to therapy. The high toxicity rate of immunotherapy in this setting also underscores the importance of identifying intracranial biomarkers of activity given the risk for adverse events in a frail patient population. The authors note that additional studies will be needed to identify specific facets of those patients’ tumors or tumor microenvironments that led to such a favorable response.