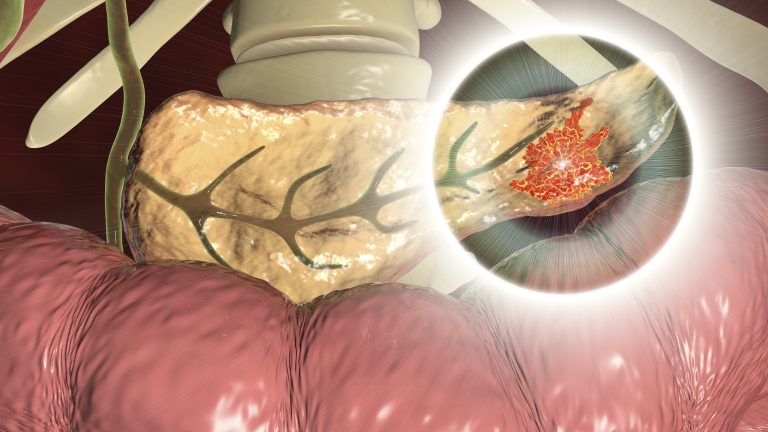

New research by scientists at Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons and Herbert Irving Comprehensive Cancer Center and with collaborators at the University of Pennsylvania, demonstrates that lowering levels of the hormone PTHrP can prevent metastases and improve survival in mice with pancreatic cancer.

“Pancreatic cancer metastasis is a leading cause of cancer-related deaths, yet very little is understood regarding the underlying biology,” wrote the researchers. “As a result, targeted therapies to inhibit metastasis are lacking. Here, we report that the parathyroid hormone–related protein (PTHrP encoded by PTHLH) is frequently amplified as part of the KRAS amplicon in patients with pancreatic cancer.”

This lack of understanding of the metastasis and lack of therapy options makes pancreatic cancer one of the most deadly, with the general five-year survival rate around 10%.

For this new study, the researchers first eliminated PTHrP from mice with pancreatic cancer using genetic engineering. They observed that metastasis was eliminated, survival was enhanced, as well as a reduction in the size of the initial tumors in the pancreas.

Survival increased from a median of 111 days to 192 days, with near complete elimination of metastases. The 73% increase in survival, the researchers said, is one of the largest observed in mice with this type of pancreatic cancer.

The researchers then tested the anti-PTHrP antibodies in human pancreatic cancer cells. They observed that among 3D organoids derived from pancreatic cancer patients under an IRB-approved protocol, anti-PTHrP antibodies reduced growth and viability of the cells.

The researchers also reported that targeting PTHrP attacks pancreatic cancer in two ways. It first reduces the ability of the tumor cells to transition from an epithelial state to a mesenchymal state. Secondly, it prevents the growth of primary and secondary tumors.

“We think these findings provide a strong rationale for further developing anti-PTHrP therapy towards clinical trials,” explained study author Anil K. Rustgi, MD. He also credits Richard Kremer, MD, PhD, of McGill University for developing the antibodies.

“We are hopeful that a drug targeting PTHrP could be used to treat most patients with pancreatic cancer,” he said, “because the vast majority have tumors with high levels of PTHrP. There is the potential application to other cancers as well.”

The researchers believe suggests a wider search for cancer-causing genes is needed.

“We feel that PTHrP may have been previously overlooked as a mere passenger gene co-amplified with KRAS, but our study shows that PTHrP has its own tumor-promoting functions,” Pitarresi said. “It suggests other so-called ‘passenger’ genes may have bigger roles in cancer than we initially thought and should be examined more closely.” Rustgi noted, “It might open up for combinatorial therapies of targeting the KRAS pathway with an antibody to PTHrP.”