An international collaboration of biomedical researchers, led by Vanderbilt University Medical Center, has identified the TCL1A gene as a driver of clonal expansion of precancerous blood cells and a possible target for blood cancer prevention.

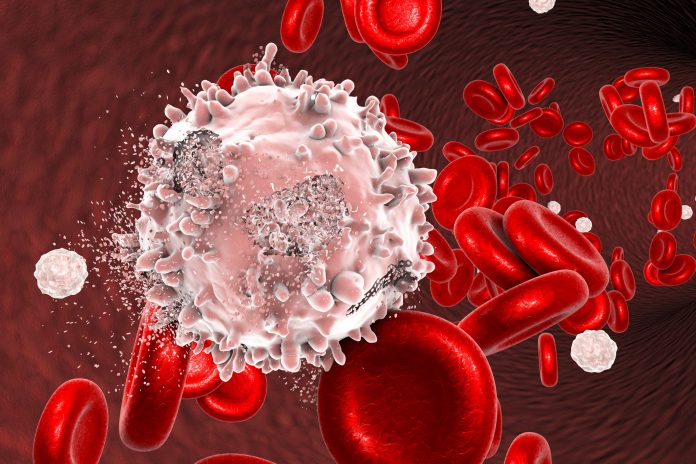

According to the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society, every three minutes, one person in the United States is diagnosed with one of the general blood cancers: leukemia, lymphoma, or myeloma. One of the causes of blood cancer is non-inherited mutations in blood stem cells that can lead to the cancerous growth of abnormal cells.

Reporting in Nature, scientists now suggest that targeting a gene called TCL1A may be able to suppress such growth and decrease the risk of blood cancer. The gene was identified using a technique called PACER which can measure the growth rate of precancerous clones of blood stem cells.

“We think that TCL1A is a new important drug target for preventing blood cancer,” said Alexander Bick, MD, PhD, the study’s co-author with Stanford University’s Siddhartha Jaiswal, MD, PhD.

PACER stands for “passenger-approximated clonal expansion rate,” meaning that the technique is able to detect passenger mutations in an individual’s blood. These mutations accumulate in cells with age but don’t provide them with any proliferative benefits. However, they can be used to determine the growth rate of blood stem cell clones.

”You can think of passenger mutations like rings on a tree,” said Bick. “The more rings a tree has, the older it is. If we know how old the clone is (how long ago it was born) and how big it is (what percentage of blood it takes up), we can estimate the growth rate.”

The researchers used the technique on more than 5,000 people who had acquired cancer-associated mutations but did not have blood cancer. Using a genome-wide association study, they were then able to identify the TCLA1 gene as a driver of increased growth rates in blood stem cell clones.

Further experimental studies showed that a commonly inherited variant of the gene, which is located in its promoter region, was linked to a slower clonal expansion rate of the blood stem cell clones and therefore reduced the prevalence of driver mutations leading to blood cancer.

“Some people have a mutation that prevents TCL1A from being turned on, which protects them from both faster clone growth and from blood cancer,” Bick said. That’s what makes the gene so interesting as a potential drug target.”

The researchers continue to investigate the role of the gene in blood cancer with the hope of discovering additional important pathways in order to possibly prevent the onset of disease in future studies.