A large international study investigating the genetics of the rare childhood muscle and soft tissue cancer rhabdomyosarcoma has revealed genetic variants linked with more severe disease that could help researchers develop better targeted therapies in the future.

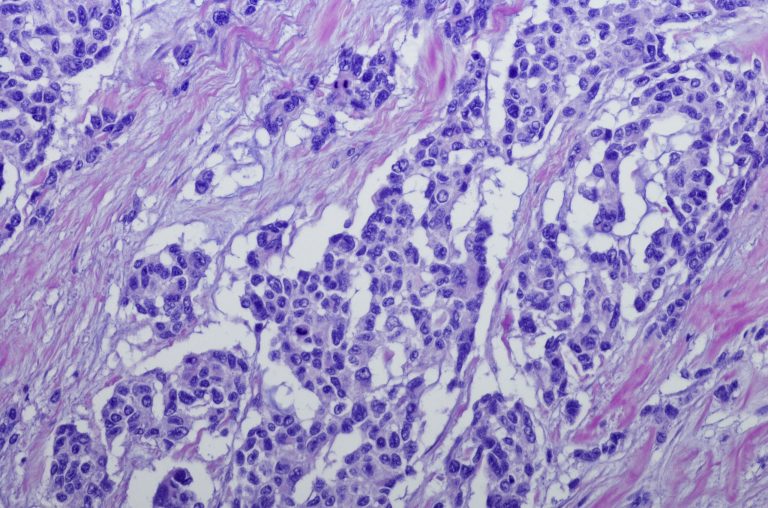

Rhabdomyosarcoma is an aggressive, but relatively rare cancer with approximately 250 cases per year in the US, mostly in those under the age of 18 years. It develops from stem cells that have not properly developed into skeletal muscle or myocyte cells.

There are four known subtypes and having a clear diagnosis is important as it impacts treatment and outcomes, which can vary from a 5-year survival rate of 35% to 95% depending on type and treatment.

Although there is a known PAX-FOXO1 fusion gene that is now screened for and is linked to a worse outcome, more information is needed about the genetics of this cancer to assess outcomes better and improve treatment choices.

“The standard therapy for rhabdomyosarcoma is almost a year of chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and surgery. These children get a lot of toxic treatments,” said the first author of the Journal of Clinical Oncology paper describing the research, Jack Shern, a researcher at the NIH Center for Cancer Research in Bethesda.

“If we could predict who’s going to do well and who’s not, then we can really start to tailor our therapies or eliminate therapies that aren’t going to be effective in a particular patient. And for the children that aren’t going to do well, this allows us to think about new ways to treat them.”

The study included 641 children with rhabdomyosarcoma from the U.K. and U.S. who were enrolled on different cancer trials and who had known survival data. Tumor samples from the patients underwent custom-capture sequencing to look for mutations, indels, gene deletions, and amplifications.

The researchers uncovered some new genetic insights from their study. In those without the PAX-FOXO1 fusion gene, more than 50% of individuals had RAS gene mutations, but this did not appear to be linked with survival. Overall, mutations in RAS oncogenes were particularly common in infants under the age of 1 year who developed the cancer, at 64%.

Mutations in the genes BCOR, NF1, and TP53 were found at higher rates than previously discovered in 15%, 15%, and 13% of cases, respectively. TP53 gene variants were associated with worse outcomes both in patients with and without the PAX-FOXO1 fusion gene, and MYOD1 gene variants in those without the PAX-FOXO1 fusion.

Patients with MYOD1 gene variants often also had variants in two other genes –PIK3CA and CDKN2A. “Our observation that MYOD1 mutations invariably co-occur with mutation in a second gene, most notably PIK3CA and CDKN2A, is consistent with a recent report,” write the authors. “The co-occurrence with CDKN2A is of interest given that a recent large survey of soft tissue sarcomas of multiple histologies… implicated CDKN2A as a biomarker of poor prognosis.”

The researchers plan to continue to investigate and validate their findings and hope they will help clinicians with treatment decision making. “These discoveries change what we do with these patients and trigger a lot of really important research into developing new therapies that target these mutations,” concluded Javed Khan, a senior researcher also based at the NIH’s Center for Cancer Research, who co-led the study.