PLK1, or polo-like kinase 1, has long been implicated as an oncogene. Evidence, much of it circumstantial, has been accumulating against PLK1 for decades. New findings, however, indicate that PLK1 may have been misjudged all this time.

According to researchers from the Spanish National Cancer Research Centre (CNIO) and the German Cancer Research Centre (DKFZ), PLK1 may function not as an oncogene, but as the exact opposite, a tumor suppressor. This surprising finding appeared August 1 in the journal Nature Communications, in an article titled, “Plk1 overexpression induces chromosomal instability and suppresses tumor development.”

Initially, the researchers sought to confirm PLK1’s oncogenic nature, which had been strongly suspected, and even presumed, but never formally demonstrated. They modified the genome of a mouse so that it was possible to overexpress the PLK1 gene at will. The first thing they noticed was that mice in which PLK1 was overexpressed did not develop any more tumors than did normal mice.

The researchers also crossed their mice with others that expressed the oncogenes H-Ras or Her2 in their breast tissue, oncogenes associated with very aggressive breast tumors. The researchers expected a much greater incidence of cancer, but the result was unexpected: by overexpressing PLK1 together with the oncogenes, the incidence of tumors was reduced drastically.

“That was when we realized that something important was happening,” says Guillermo de Cárcer, Ph.D., a CNIO researcher and the lead author of the new study. Intrigued, the researchers uncovered details that showed how PLK1 may act as a tumor suppressor.

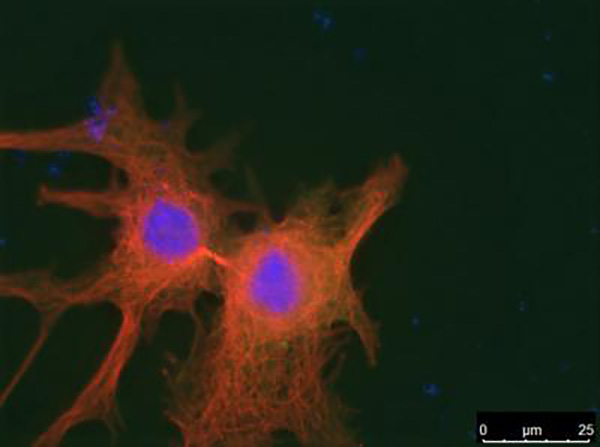

“Plk1 overexpression results in abnormal chromosome segregation and cytokinesis, generating polyploid cells with reduced proliferative potential,” the Nature Communications article indicated. “Mechanistically, these cytokinesis defects correlate with defective loading of Cep55 and ESCRT complexes to the abscission bridge, in a Plk1 kinase-dependent manner. In vivo, Plk1 overexpression prevents the development of Kras-induced and Her2-induced mammary gland tumors, in the presence of increased rates of chromosome instability.”

These findings prompted the researchers to consult the breast cancer databases, in search of a link between the expression of PLK1 and patient prognosis. According to Dr. de Cárcer, this work confirmed that “the expression of Plk1 can result in a very different type of prognosis depending on the tumor subtype.”

In Her2-positive tumors, the expression of PLK1 gives a better prognosis; however, in patients with positive tumors for the expression of the estrogen receptor, it's the complete opposite.

If Plk1 can act as a tumor suppressor, does that call into question therapeutic strategies that are based on the inhibition of Plk1? Not necessarily, concludes the CNIO/DKFZ team. “Many essential components of cell proliferation may be used as cancer targets despite having no oncogenic activity,” they explained in their paper, “owing to the non-oncogene addiction of cancer cells for specific cellular processes such as cell division.”

The researchers also suggested that their work may enhance the value of the PLK1 gene as an oncological biomarker. “Understanding when PLK1 acts as an oncogene or as a tumor suppressor, and in which types of tumors this happens, is clinically extremely relevant when it comes to using this gene as a therapeutic biomarker,” noted de Cárcer.

“Plk1 is a frequent hit in chemical or genome-wide genetic screens to uncover new targets under different oncogenic backgrounds,” the authors of the Nature Communications article pointed out. “Understanding the specific requirements for Plk1 as compared to other essential cell cycle kinases will likely contribute to a better design of therapeutic strategies against its kinase activity.”