New findings from researchers at Linköping University in Sweden have shown that contrary to previous belief, stems cells remain in the bone marrow in acute lymphocytic leukemia. The disease, however, has been found to cause a hidden defect in the stem cells, that makes them lose their ability to form new blood cells—providing an explanation for why survivors experience negative effects on blood formation decades after they have been cured.

“It’s estimated that a normal person produces so many blood cells in a lifetime that these could fill a large passenger aircraft. As many of the cells in our blood have a short life span in our bloodstream, new blood cells are constantly formed so that we can stay healthy,” said Mikael Sigvardsson, professor in the Department of Biomedical and Clinical Sciences (BKV) at Linköping University and professor in the Division of Molecular Hematology at Lund University.

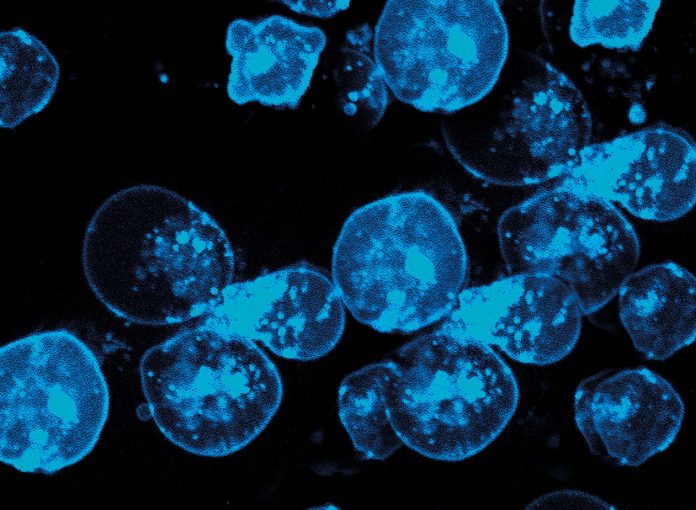

Sigvardsson’s research has centered on the blood cancer called B-cell acute lymphocytic leukemia, or B-ALL. In this cancer, a B cell, which normally produces antibodies involved in immune response, has stalled at an intermediate stage in its development resulting in uncontrolled cell division. As more of these are formed, they crowd the tight confines in the bone marrow disrupting the normal formation of new blood cells. Symptoms of this activity include anemia, due to the reduction of oxygen-transporting red blood cells, increased risk of infection due to immune cell deterioration, and bruising and bleeding as a lack of platelets in the blood hampers the body’s ability to form blood clots.

The prevailing opinion has been that reduced blood formation in leukemia may be due to cancer cells forcing blood stem cells out of the bone marrow. But the recent study by Sigvardsson’s team, published in Haematologica, shows that this is incorrect.

“We saw that the blood stem cells were still in the bone marrow. This could explain why good blood formation is quite quickly restored in a significant share of B-ALL patients once treatment has started and the number of cancer cells has been reduced. But the various intermediate stages in blood formation disappeared,” noted Sigvardsson.

For their research, the Linköping University investigators used a mouse model of B-ALL to determine which blood cells types were the first and last to disappear during the development of the disease. To do this, the researchers counted the various cell types by leveraging the unique protein combination found on the cell surface of different cell types. The researchers also analyzed cells from the bone marrow of 19 B-ALL patients and obtained corresponding results, showing that the number of blood stem cells remained the same also in advanced stages of the disease.

It is known that many B-ALL survivors have blood cell function problems later in life, often experienced as immune system flaws. In some cases, a small number of stem cells can become dominant in producing all the blood cells in the body—in extreme cases from only one stem cell. This is often due to mutations in the blood stems cells that make them grow better than other cells. These mutations may have been caused by chemotherapy used to treat the original leukemia and may also be the first stage in developing new cancer.

However, the current study, shows that the leukemia itself is responsible for the defects found in blood stem cells. The researchers observed that when they transplanted blood stem cells from mice with leukemia to healthy mice that the stems cells functioned properly initially, but after several months, the stems cells began to disappear and could no longer form blood.

“It seems that the remaining stem cells have a functional damage that can’t be seen until long afterwards,” Sigvardsson said. “We think that this could explain some of the long-term effects seen in certain adults having survived childhood cancer.”