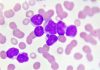

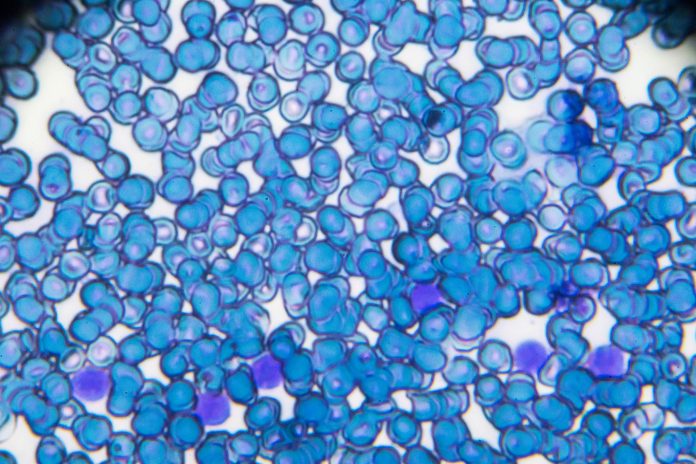

A new test helps predict which myeloma patients will benefit most from lenalidomide (Bristol Myers Squibb’s Revlimid), which is often used to prevent relapse after a stem cell transplant.

For myeloma patients with certain high-risk genetic features in their cancer cells, this drug cuts their risk of seeing their cancer progress or dying by up to 40-fold. But patients with “double hit” mutations, the researchers write, still are “… in urgent need of novel maintenance approaches.”

The study, published in Blood, was led by scientists at The Institute of Cancer Research (ICR), London, in collaboration with the clinical trials unit at Leeds University.

Study leader Martin Kaiser of the ICR said, “We have found a new way to predict which patients with newly diagnosed myeloma are most likely to benefit from the cancer drug lenalidomide after undergoing a bone marrow transplant. We believe that genetic profiling should be routinely used in myeloma treatment. Knowing which high-risk genetic features are present in each cancer can help us make the best choices.”

Approximately one quarter of myeloma patients have various high-risk genetic features. These genetic features can make the cancer more aggressive, less responsive to treatment and likely to relapse more quickly.

In this study, researchers analyzed data from 566 patients from the Myeloma XI trial, which aims to evaluate the effectiveness of a range of targeted drugs, including lenalidomide, in people with newly diagnosed myeloma.

Out of the 556 patients, 17 percent had “double hit” myeloma (meaning they had two or more high-risk genetic features), 32 per cent had only one high-risk genetic feature, and 51 percent had no high-risk markers.

ICR researchers analyzed these groups and found that some single-hit myeloma patients benefited the most from lenalidomide maintenance therapy after a stem cell transplant– specifically, those with three different genetic abnormalities known as del(1p), del(17p) or t(4;14).

These patients had an up to 40-fold reduced risk of cancer progression or death, compared to those on observation alone.

Patients with one of these “single-hit” genetic abnormalities lived longer on lenalidomide maintenance therapy–for an average almost five years before their disease progressed, compared to 10.9 months for those on observation alone.

Those with “double hit”or no high-risk genetic markers also saw some benefit from lenalidomide. They had around a two-fold reduced risk of disease progression or death compared to observation, respectively. However, patients with a different “single-hit” genetic marker known as gain(1q) seemed not to derive consistent benefit from lenalidomide, suggesting this group may be more complex than others.

These findings support the use of lenalidomide in myeloma patients who have undergone a stem cell transplant, especially those with single-hit high-risk markers like del (1p), del(17p) or t(4;14)–as well as the use of routine genetic testing in people with myeloma, to identify those most likely to benefit from different treatment strategies.

Shelagh McKinlay, Director of Research and Advocacy at blood cancer charity Myeloma UK, said, “This research is absolutely vital and brings us closer to a more personalized approach to treatment, which is key for myeloma patients as it is such an individual cancer.”