By Frieda Wiley

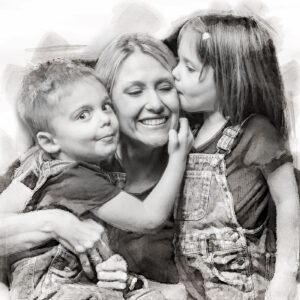

Treating chronic illnesses usually saves lives. However, when that condition lacks a billing code, seeking treatment can become a death sentence. At least that’s what doctors told Amber Freed, a 43-year-old mother of two who learned that something seemingly as trivial as a billing code could become a life-or-death situation.

It all began shortly after Freed gave birth to fraternal twins Maxwell and Riley in March 2017. The newly found joys of motherhood quickly transformed into fear after she observed marked differences between her two children’s developmental progression.

“I noticed Riley was advancing faster than Maxwell,” she said, “[Maxwell] had strange movements, his eyes were open, and he didn’t know his name,” she recalls.

He also felt different in her arms. “He felt floppy to me compared to Riley.”

Freed could easily fill Riley’s baby book with fun memories and important milestones. Meanwhile, Maxwell’s book lacked a similar narrative and remained largely empty.

Maternal instincts trump a doctor’s experience

Worried, the new mother took her son to his pediatrician, who immediately dismissed her concerns. He assured her Maxwell was progressing normally, telling her that girls develop faster than boys. Still, Freed could not shake the feeling that something was wrong. Her gnawing gut instinct prompted her to schedule an appointment at the Children’s Hospital in Denver, Colorado, where the family lived. There, Maxwell saw a variety of specialists, including an ophthalmologist who gave Freed some startling news after conducting an eye exam on Maxwell.

“His eyes are fine, but I think you should be prepared for him not to live,” he told her.

Completely floored, Freed asked the doctor what he had seen in the exam.

“I saw nothing,” the doctor reiterated. “However, I see parents like you all day long searching for answers and thinking something’s wrong with their kids’ eyes when it’s really their brain.”

Her greatest fears now confirmed, Freed struggled to maintain her composure as she prepared to take her son in for additional testing.

The ophthalmologist’s feedback eventually led to a diagnosis she could never have fathomed. Maxwell had an SLC6A1 mutation that causes epilepsy—a condition so rare it had no name, let alone a cure. Lacking a moniker also meant limited funding for research or other supportive services.

In addition to many of these conditions being incurable or lacking sufficient treatments, patients and their families often struggle to pay for treatments at times because no International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes have been developed for the conditions they face. The World Health Organization has ownership of the ICD codes, which are designed to track morbidity and mortality data. However, the U.S. health insurance industry has commercialized the codes by using them for billing and payment.

As Freed would soon learn, securing medical treatment for the kind of rare disease Maxwell had would prove quite challenging in the U.S. Rare conditions such as Tay-Sachs disease, hereditary hemochromatosis, Wilson’s disease, and cystic fibrosis are all rare conditions with ICD codes recognized by insurance companies for coverage. Yet, these conditions may be more of the exception than the rule. In the U.S., many other diseases the lack billing codes that insurance companies would use to provide financial coverage and reimbursement. The void amplifies a climate where the privatized and commercialized insurance system fragments healthcare coverage as much as the lack of universally available medical records fractures continuity of care.

“If we were living in Europe, Maxwell’s treatment would be covered because of the nationalized medical systems they have there,” she said.

In addition to the rarity of her son’s condition decreasing the chances of insurance coverage, Freed made another startling discovery. Many billing codes covered seemingly bizarre and rare injuries. Yet not a single billing code acknowledged her son’s nameless condition in any way. Lacking a billing code meant insurance would neither pay for nor reimburse any treatment.

“It’s funny,” she said. “There’s an International Classification Code (ICD)-10 for being bitten by a goose, but there’s no code to treat my child for his condition.”

According to the ICD-10.CM, the code, known as W61.51XD, “describes the circumstance of the injury,” if a goose attacks a person. Goose-inflicted injury is one of many billing codes one might not expect to see listed. Other bizarre ICD-10 codes include Y93.J1, which covers neck injuries from playing the piano, and V97.21, which applies to a parachutist involved in an accident. Billing code V91.07XD addresses burns caused by water skiing and 16.V97.33XD describes a “subsequent encounter” of getting sucked into a jet engine. Curiously, Y92.146 describes a “swimming-pool of prison as the place of occurrence of the external cause.”

Pediatric Emergency Medicine physician The American Academy of Pediatrics

According to Jeffrey Linzer, Sr., MD, a pediatric emergency medicine physician representing the American Academy of Pediatrics, the origins of the seemingly bizarre billing codes stem from a very unlikely source: the U.S. Congress.

“Congress directed the Department of Defense to create a distinction between codes for the military versus non-military,” he told Inside Precision Medicine. “In fact, they recommended 10,000 codes.”

It’s all about the Benjamins

As incredulous as it sounds, Freed’s challenges are not unique. Many patients and families of people with rare diseases living in the U.S. face the same challenge.

The National Institutes of Health defines a rare disease as a disease affecting less than 200,000 people living in the U.S. However, rare diseases have a substantially greater collective impact, affecting 25–30 million U.S. residents. Despite the sizeable total population affected, the prognosis looks grim for most of these 10,000-plus rare diseases as only 500 of them have any type of treatment.,

In addition, the few treatments available often prove far more expensive than the average cost of treating more common chronic conditions in the U.S. According to the U.S. Government Accountability Office, costs for treating rare diseases in the U.S. approached nearly $966 billion in 2019.

When a rare disease affects a child, parents and other caregivers must often assume the costs while juggling additional responsibilities of advocating for their patients and the disease itself while becoming both caregivers to the child and educators to medical professionals, the federal government, and other stakeholders. The arduous undertaking has a sizeable impact on the rare disease community as children account for 50% of people diagnosed with a rare disease.3 Disturbingly, three out of ten children diagnosed with a rare disease will die before their fifth birthday.

“The doctors told me, ‘You will become the expert’,” recalled Freed.

The growing list of insurmountable obstacles Freed faced became overwhelming. Doctors told Freed that she would likely have to give up her burgeoning career to devote herself full-time not only to her son’s care but to educating herself—and others—on the condition. She eventually resigned from her position as an equity and research analyst at a financial firm.

Freed’s fastidious search for solutions ultimately led to a partnership with a scientist to develop a gene therapy for her son, but the clinical trial was halted during the COVID-19 pandemic. In the interim, her son has been receiving injections of an off-label therapy called glycerol phenylbutyrate (Ravicti®). While not a cure, it makes Maxwell’s signs and symptoms more manageable.

When the Food and Drug Administration first approved the drug for urea cycle disorder on February 1, 2013, its cost ranged between $250,000 and $290,000 annually. However, the price skyrocketed once doctors began prescribing it off-label to treat Maxwell’s condition. As of early 2024, glycerol phenylbutyrate ranks among the top ten most expensive therapies in the U.S., costing nearly $800,000 annually for its on-label indication.

Even the cheaper option doesn’t run cheap

“The effect of glycerol phenylbutyrate on children with SLC6A1 is compelling,” Zachary Grinspan, MD, a pediatric neurologist at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York City, told Inside Precision Medicine. “[However, the manufacturer], Horizon Therapeutics, did not pursue a new clinical indication, and Amgen’s strategy is unclear.”

pediatric neurologist

Weill Cornell Medicine, New York City

Prescriptive authority allows Grinspan to prescribe glycerol phenylbutyrate, but it does not fill the void of the noticeably absent ICD-10 code from Maxwell’s medical charts. Insurance companies are less likely to cover a drug written for an off-label indication—especially for such a high-dollar drug.

In the meantime, Grinspan aims to get the drug listed in one of the U.S. four drug compendia (i.e., American Hospital Formulary Service-Drug Information [AHFS-DI], Micromedex DrugDEX [DrugDEX], National Comprehensive Cancer Network [NCCN] Drugs, and Biologics, Compendium, and Clinical Pharmacology) to help increase awareness of the drug.

Although a beneficial treatment, the positive effects of glycerol phenylbutyrate therapy wear off after about a year. Much like developing gene therapy for her son, Freed will continue facing the obstacle of footing the six-figure cost.

ICD-10: the rate-limiting step to treatment, access, and potential cures

Unlike many other developed countries with universal healthcare systems, the privatization of insurance contributes to soaring medical costs. This in turn often makes access to care and treatments cost-prohibitive. However, the federal government also plays a role in this narrative as they oversee the ICD-10 codes.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) is responsible for tracking mortality and morbidity information at a national level and using the data to generate information on disease incidence and prevalence. The process is relatively simple for chronic diseases affecting the masses, such as hypertension or diabetes, as these conditions have ICD-10 codes.

The Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services, commonly known as CMS, develops and maintains what is known as the International Classification of Diseases, 10th, Revision, Procedure Coding System (ICD-10-PCS). The CMS classifies treatment for diseases, impairments, and injuries for patients who are hospitalized. However, the approval of coding changes and other changes to the ICD-10 coding systems is a collaborative process between the CMS and the CDC’s National Centers for Health Statistics through a body known as the ICD-10 Coordination and Maintenance Committee. This interdepartmental committee meets biannually and accepts modification suggestions from both the public and private sectors.

“There are only two opportunities to apply for the code, and your application may not even be reviewed given that there’s no formal process,” Freed said.

Could another rare disease change the game?

Although many rare diseases remain unassigned, the success of another rare disease may offer a blueprint for successful ICD-10 applications in the rare disease community.

According to data published in 2022, assigning Angelman syndrome an ICD-10 code on October 1, 2018, resulted in a significant uptick in adoption and uptake in the three years following its release. Billed under ICD-10 code Q93.51, a wide variety of clinicians, including pediatric neurologists, geneticists, and developmental-behavioral medicine specialists, now use this code. In addition, the top five healthcare organizations using the billing code gained prescribing privileges at major medical institutions in the U.S., including the Children’s Medical Center Dallas, the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center- Community, and Massachusetts General Hospital.

The Angelman syndrome ICD-10 code assignment results give Grinspan hope for a potential strategy to overcome the ICD-10 code void for SLC6A1.

“For people with rare epilepsies, improving epidemiological estimates and clinical descriptions will guide clinical diagnosis and management, support research initiatives, spur pharmaceutical and medical device development, and help families understand these devastating diseases,” Grinspan said. “ICD-10 codes for specific rare epilepsies are foundational for that effort.”

Grinspan further elaborated that the statistical data captured by the CDC helps clinicians prioritize testing when working up new patients and conduct more thorough workups. This enhances their ability to comprehensively evaluate the patient. Robust data therefore enhances the physicians’ ability to diagnose a condition and forecast the patient’s prognosis.

In addition to the ICD-10 code, clinical trials, and funding, physicians need education to improve outcomes

Clinical trials could support treatment and provide more long-term data for diseases as ultra-rare as Maxwell’s. However, clinical trials in children with rare diseases often prove more complex as they require considerations transcending those typically seen in trials for adults. Parents and caregivers often face higher demands in managing the child, observing and helping the children report their signs and symptoms, and sometimes acting as key decision-makers when enrolling a child into a clinical trial.

Historically, commercial sponsors have been less likely to support clinical trials involving child participants than those involving adults. This trend further amplifies cost woes, as pediatric trials may require more study sites and accrue additional costs for coordination. In addition, clinical trials for rare diseases are typically underpowered due to difficulties in recruiting an ample number of participants.

Various other factors inflate the cost of pediatric clinical trials. For example, they may require more time to complete study procedures and specialized (and therefore pricier) laboratory equipment that can accommodate smaller-volume biological samples. Off-label prescribing of treatments occurs much more frequently in pediatric patients, shrinking potential incentives that might entice funders to finance drugs that are already approved for the adult population. These are just a few factors unique to the pediatric population contributing to the already hefty price tags associated with clinical trials.

Pediatric population aside, clinical trials are costly regardless of the number of enrollees or disease state. In addition to population-specific idiosyncrasies, the number of sites, the anticipated number of enrollees, and phases play a factor. Lastly, the cost of the type of therapy (i.e., small molecule versus large molecule, gene therapy, etc.) is a significant factor affecting the total cost.

According to Kimberly Goodspeed, MD, assistant professor in the departments of pediatrics, neurology, and psychiatry at UT Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas, small molecule clinical trials like one involving glycerol phenylbutyrate can range from $25 million to $50 million.

Trials investigating gene therapies cost significantly more.

“You can imagine if you could enroll multiple disorders into a blanket protocol for one multi-site clinical trial at $50 million versus doing ten disorders with individual protocols at $50 million per individual protocol, the costs can climb quickly—especially in the case of gene therapy,” said Goodspeed.

Even if clinical trials were not cost-prohibitive, there remains the clinician factor. From a practical standpoint, many physicians already feel overwhelmed by the need to memorize ICD-10 codes. As Linzer stated during on March 9, 2023, during the ICD-10 Coordination & Maintenance Committee Meeting led by CMS, committing countless ICD-10 codes to memory for each rare disease may not be plausible.

“We’re very sympathetic to [the cause], but that’s not the issue,” he told the audience. “Our concern is the number of potential patients and developing unique codes for a tiny group of patients.”

Linzer went on to cite situations where proposals for larger populations were denied, as examples.

“If this proposal was to move forward, we certainly have already expressed our disagreement with the expansion to the sixth character on the ‘under the epilepsy [category]’ … but we do have concerns about unique codes for very small patient populations,” he said. “We understand it’s helpful in the research and clinical areas, but it’s just an issue of how many codes can there be?”

In a separate interview with Inside Precision Medicine, Linzer stated that creating additional codes can create problems in data tracking. Problems arise when the medical community uncovers additional information about a condition that leads to code expansion. Because the original intent of the code is to track morbidity and mortality, the code cannot be deleted.

Now approaching his seventh birthday, Maxwell Freed has already beat the odds that claim nearly one-third of children with a rare disease succumbing to their condition before their fifth birthday. Yet, the battle is far from over, as his mother, and countless other parents, continue advocating for their children in search of Federal support and cures.

“Mothers can pull from a source of energy that doesn’t exist,” Freed said of her ongoing efforts. “You hold your baby and know there’s nothing you wouldn’t give.”

As of press time, Freed’s applications for an ICD-10 assigned to SLC6A1 have remained unsuccessful and she received her most recent rejection in early 2024. Meanwhile, her son’s life—and those of others—hang in the balance.

Her solution? “I’ve learned how to fight like a mother.”

A mother’s enduring love is unmatched, and mothers never give up.

Read more:

- What We Do. The National Institutes of Health website. Accessed on February 25, 2024.

- The Promise of Precision Medicine: Rare Diseases. The National Institutes of Health website. Accessed on February 28, 2024

- Numbers: Rare Disease Facts. The Global Genes website. Accessed on February 28, 2024.

- Rare Disease: Although Limited, available Evidence Suggests Medical and Other Costs Can Be Substantial. The U.S. Government Accountability Office website. Accessed on February 28, 2024.

- Guha, M. Urea cycle disorder drug approved. Nat Biotechnol 31, 274 (2013).

- “The 10 Most Expensive Drugs on the Market.” The Talk to Mira website. Accessed on February 28, 2024.

- ICD-10 Coordination and Maintenance Committee. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Last reviewed October 17, 2022. Accessed on February 24, 2024.

- Kamada’s Prism Healthcare Map. Prism 2022.

- Kern SE. Challenges in conducting clinical trials in children: approaches for improving performance. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2009 Nov 1;2(6):609-617. doi: 10.1586/ecp.09.40. PMID: 20228942; PMCID: PMC2835973.

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Clinical Research Involving Children; Field MJ, Behrman RE, editors. Ethical Conduct of Clinical Research Involving Children. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2004. 2, The Necessity and Challenges of Clinical Research Involving Children.

Frieda Wiley, PharmD, is an award-winning medical writer, best-selling author, speaker, and pharmacist who has written for O, Oprah Magazine, the National Institutes of Health, American History, Pfizer, Merck, AstraZeneca, and many more notable organizations.