A new radiology study using an advanced MRI technique demonstrates that the structural integrity of the brain’s white matter is lower in cognitively normal people who possess a genetic mutation associated with Alzheimer’s disease than it is in those who don’t harbor the mutation. The study findings support a potential role for imaging-based identification of structural changes of the brain in people at genetic risk for early-onset Alzheimer’s disease in understanding how genes influence the disease process that leads to dementia.

“This shows the potential of MRI as an evaluation tool in patients who are deemed at-risk for Alzheimer’s disease before they develop symptoms,” said lead author Jeffrey W. Prescott, M.D., Ph.D., neuroradiologist at the MetroHealth Medical Center, Cleveland. “Use of these advanced MRI techniques could help further refine identification of at-risk patients and risk measurements.”

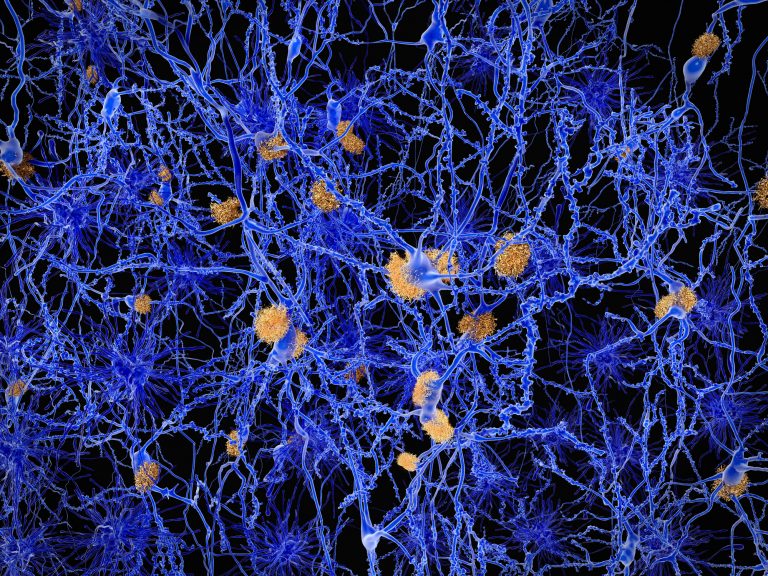

People with the autosomal dominant Alzheimer disease (ADAD) mutation are known to have a higher risk of Alzheimer’s disease, the mutation is linked to a buildup of abnormal protein called amyloid-beta in the brain that affects both the gray matter and the signal-carrying white matter.

“It’s thought that the amyloid deposition in the gray matter could disrupt its function, and as a result the white matter won’t function correctly or could even atrophy,” said lead author Jeffrey W. Prescott, M.D., Ph.D., neuroradiologist at the MetroHealth Medical Center, Cleveland.

Prescott and colleagues had conducted an earlier study on patients with sporadic Alzheimer’s disease—which comprises 99% of cases—and determined that white matter structural connectivity, as measured with an MRI technique called diffusion tensor imaging (DTI), degraded significantly as patients developed more amyloid burden.

“The current work extends these results by showing that similar findings are detectable in asymptomatic at-risk patients,” added Jeffrey R. Petrella, M.D., professor of radiology at Duke University and senior author on both studies.

For the new study, researchers used data from the Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network (DIAN) to compare ADAD mutation carriers with non-carriers to see if there were changes in structural connectivity that could be related to the mutation. Study participants included 30 mutation carriers, mean age 34 years, and 38 non-carriers, mean age 37. All exhibited normal cognition when they underwent structural brain MRI and DTI.

Analysis showed that people carrying the AD-associated mutation had lower structural connectivity in the frontoparietal control network, which connects areas mainly in the parietal and frontal lobes, two regions known to be involved with Alzheimer’s disease. Among mutation carriers, there was a correlation between expected years until onset of symptoms and white matter structural connectivity in the frontoparietal control network, even when controlling for amyloid plaque burden.

“We used a network measurement called global efficiency, in which a decreased efficiency can be taken as a breakdown in the organization of the network,” Prescott said. “The results show that for mutation carriers, global efficiency would decrease significantly as they approach the estimated age of symptom onset.”

In addition to helping determine the timing of disease onset, the findings also point to a role for imaging in studying therapeutic drugs to treat Alzheimer’s disease. While the majority of trials so far have been performed with patients who already have Alzheimer’s disease or cognitive impairment, earlier identification and treatment of patients at risk represents a more promising avenue for preventing or at least delaying the onset of dementia.

“One potential clinical use of this study tool would be to add quantitative information to risk factors like family history and use that to help identify patients early, when they may benefit from treatment,” Prescott said. “But until we have an effective treatment, we will have to wait for that to be implemented.”

The researchers intend to do follow-up study using advanced imaging and updated data from the DIAN network to evaluate the progression of Alzheimer’s disease in the study participants.