Heart disease in women is underdiagnosed compared to men. Now, more accurate cardiovascular risk models for women have been developed by U.S. and Netherlands researchers using a dataset of more than 20,000 participants in the UK Biobank. This team also quantified the underdiagnosis of heart disease in women. They say their study provides a first step for rethinking risk factors for heart disease.

Their results were published in Frontiers in Physiology, and the lead author is Skyler St. Pierre, a researcher at Stanford University’s Living Matter Lab.

“We found that that sex-neutral criteria fail to diagnose women adequately. If sex-specific criteria were used, this underdiagnosis would be less severe,” said St. Pierre. “We also found the best exam to improve detection of cardiovascular disease in both men and women is the electrocardiogram (EKG).”

A popular scoring system used to estimate how likely a person is to develop a cardiovascular disease within the next 10 years is the Framingham Risk Score. It is based on factors including age, sex, cholesterol levels, and blood pressure.

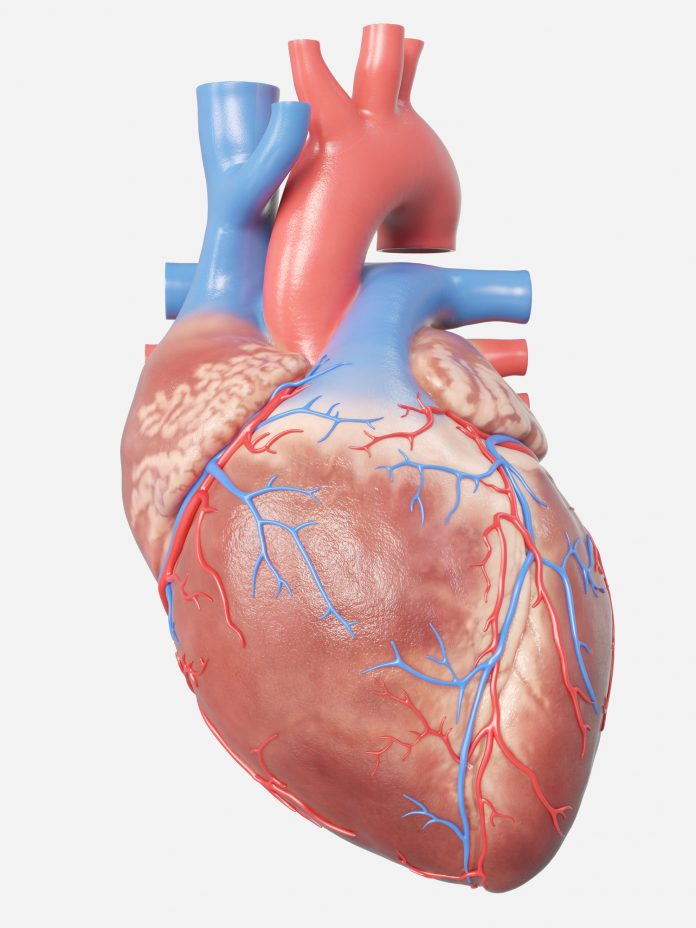

Anatomically, female and male hearts are different. For example, female hearts are smaller and have thinner walls. Yet, the diagnostic criteria for certain heart diseases are the same for women and men, meaning that women’s hearts must increase disproportionally more than men’s before the same risk criteria are met.

When these researchers quantified the underdiagnosis of women compared to men, they found that the use of sex-neutral criteria leads to severe underdiagnosis of female patients.

“Women are underdiagnosed for first degree atrioventricular block (AV) block, a disorder affecting the heartbeat, and dilated cardiomyopathy, a heart muscle disease, twice and 1.4 times more than men, respectively,” St. Pierre said. Underdiagnosis of women was also found for other heart disorders.

To achieve more accurate predictions for both sexes, these scientists leveraged four additional metrics that are not considered in the Framingham Risk Score: cardiac magnetic resonance imaging, pulse wave analysis, EKGs, and carotid ultrasounds. They used data from more than 20,000 individuals in the UK Biobank who had undergone these tests.

“While traditional clinical models are easy to use, we can now use machine learning to comb through thousands of other possible factors to find new, meaningful features that could significantly improve early detection of disease,” explained St. Pierre. Just 10 years ago, these methods were not available, which is why assessment scales like the Framingham Risk Score have been used for half a century.

Using machine learning, the researchers determined that of the tested metrics, EKGs were most effective at improving the detection of cardiovascular disease in both men and women. This, however, does not mean that traditional risk factors are not important tools for risk assessment, the researchers said.

There is still a lot of progress to be made. “While sex-specific medicine is one step in the right direction, patient-specific medicine would provide the best outcomes for everyone,” St. Pierre concluded.