Researchers based at the University of California San Diego (UCSD) have developed an app that can scan people’s pupils to search for early signs of neurological conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease, as well as other cognitive disorders.

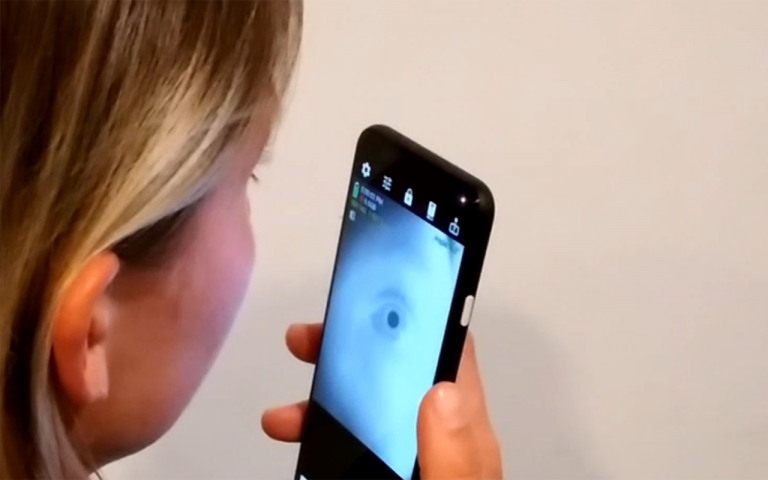

The app makes use of the near-infra red camera, which is installed in many newer smart phones for the purposes of facial recognition, to scan a user’s eyes.

“While there is still a lot of work to be done, I am excited about the potential for using this technology to bring neurological screening out of clinical lab settings and into homes,” said Colin Barry, an electrical and computer engineering Ph.D. student at UC San Diego and the first author of the paper published as part of the 2022 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, in a press statement.

“We hope that this opens the door to novel explorations of using smartphones to detect and monitor potential health problems earlier on.”

The size of the pupils in the eye is linked to various aspects of health including cognition, arousal, emotion and state of intoxication. “This connection between pupillary response and neurological processes has led to clinical research around how pupillary response is connected to neurological diseases like Alzheimer’s disease, schizophrenia, and Parkinson’s Disease,” write Barry and co-authors.

Research results confirm that changes to the pupils could be an indicator of neurological conditions like Alzheimer’s disease, schizophrenia and ADHD, among others. However, more data is needed to make this kind of assessment more widespread and accurate.

“Unfortunately, clinical grade pupillometers that work on a wide variety of eye colors and at an approachable cost are not widely available and much of the findings cannot be translated towards end-consumer and at-home patient use,” explain the authors.

To try and combat this and make this kind of neurological disease assessment more accessible, Barry and colleagues have developed a smartphone app that is able to use the phone’s near-infrared camera to measure the pupil using sub-millimeter accuracy, regardless of eye color.

The researchers compared the readings taken from the app to those taken from a more expensive pupillometer machine, which is commonly used to make these kinds of measurements, and they were similar. The system achieved a median mean absolute error of 0.27mm for absolute pupil dilation tracking and a median error of 3.52% for tracking change in pupil dilation in comparison to a standard pupillometer.

While developing the app the team tried to iron out possible user problems such as those that might be encountered by older adults with less smartphone experience.

“By testing directly with older adults, we learned about ways to improve our system’s overall usability and even helped us innovate older adult specific solutions that make it easier for those with different physical limits to still use our system successfully,” said UCSD computer engineering professor Edward Wang, who led the research at the university’s digital health lab.

“When developing technologies, we must look beyond function as the only metric of success, but understand how our solutions will be utilized by end-users who are very diverse.”

The researchers are now planning to test the app further as a possible risk screening tool for early-stage Alzheimer’s disease in older adults with mild cognitive impairment.