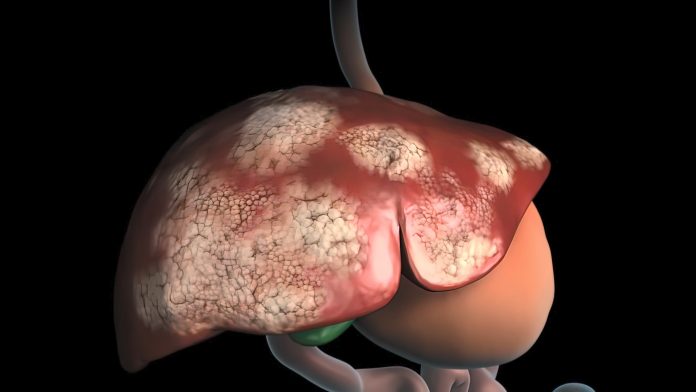

A new study reveals that circadian clock proteins are actively involved in the development of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and provide a mechanistic explanation for how liver cancer cells use these proteins to grow. The research, published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, also found that inhibiting key clock proteins can prevent cancer cells from multiplying.

Senior author Steven Kay, PhD of the Keck School of Medicine of USC has spent his career understanding the molecular components of the circadian clock, which influences much more than our sleep cycles. “We, along with many other labs, have been studying all the different functions that the circadian clock regulates, especially in the liver, because we know that our circadian rhythm really regulates a lot of aspects of glucose and lipid metabolism,” said Kay. His team has previously done the same in glioblastoma and they became aware of a significant amount of correlative data that connected circadian dysfunction with liver cancer.

“It turned out that if you start mutating circadian cycle genes, you can actually induce hepatocellular carcinoma in mice livers,” Kay explained. While an interesting observation, Kay dug deeper to see if he could identify a specific target or types of patients who might respond to drugs against clock proteins. “We wanted to learn more about early-stage translation in HCC and figure out pathways and targets within those pathways that could present novel opportunities to develop experimental therapeutics.”

In the team’s experiments, they manipulated several circadian cycle proteins in cell lines derived from human liver cancer patients and found that two key clock proteins, known as CLOCK and BMAL1, are critical for the replication of liver cancer cells in cell culture. When CLOCK and BMAL1 are suppressed, cancer cells’ replication process was interrupted—ultimately causing cell death, or apoptosis. “This discovery started us thinking more specifically about clock proteins, and how we might want to target them,” said Kay. “We wanted to identify some of the additional players in the circuit boards.”

To do so, the team drew on their collection of genomic samples, built through years of research on circadian clock proteins in the body, to further understand the role of CLOCK and BMAL1. Among other findings, they showed that eliminating the clock proteins reduced levels of the enzyme Wee1 and increased levels of the enzyme inhibitor P21.

“Wee1 is a gas pedal for cancer cells to divide rapidly and P21 is a brake pedal gene,” Kay explained. In HCC, the cancer cell has evolved to use CLOCK and BMAL1 to press hard on that gas pedal and suppress the brake pedal. But when the team genetically inhibited CLOCK and BMAL1, they team found that P21 was even more active. “So not only were we taking the foot off the gas and inhibiting Wee1, but we were also increasing P 21 activity to put a brake pedal on cancer cell division,” he added. “It’s a double whammy.”

Finally, the researchers tested their findings in vivo. Mice injected with unmodified human liver cancer cells grew large tumors, but those injected with cells modified to suppress CLOCK and BMAL1 showed little to no tumor growth.

“This paper presents a basic science landscape and presents us with the challenge that what we will need to do now quickly moving forward is to develop drugs that inhibit CLOCK and BMAL1,” Kay said, adding that his team plans to study some inhibitors already in the freezers from their work in glioblastoma.

The team also hopes to learn more about which HCC patients will benefit from a circadian treatment, along with other cancers like leukemia and colorectal cancer.

“We’re on the cusp of change where we’re going to tackle these diseases that have unmet medical need,” Kay concluded. “We need to learn how universal these abnormal CLOCK proteins are in all types of liver cancer and see if we can identify these cases that are more likely to benefit from circadian therapy.”