A new mouse model may help explain how depression and prolonged and severe stress increase heart disease risk and affect response to lipid-lowering drugs. The researchers say this is the first study to use a mouse model of chronic stress and depression to investigate whether and how chronic stress may affect cholesterol-lowering medications.

The study was led by Özlem Tufanli Kireccibasi, PhD, a postdoctoral fellow at the Cardiovascular Research Center at NYU Grossman School of Medicine in New York City. It was presented at the American Heart Association’s recent Vascular Discovery: From Genes to Medicine Scientific Sessions.

“Previous research has shown major depressive disorders and anxiety due to prolonged and severe stress have been associated with an increased rate of cardiovascular disease. The risk of developing cardiovascular disease increases in proportion to depression severity,” said Kireccibasi. “When both a major depressive disorder and cardiovascular disease are present, the prognosis is worse for both conditions.”

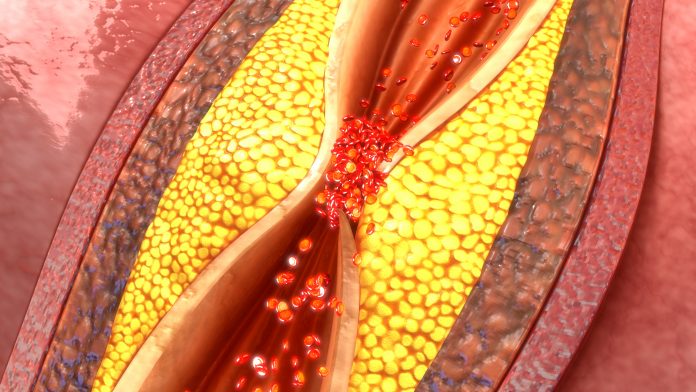

The researchers examined mice lacking a low-density lipoprotein receptor (LDLr), which is required to clear LDL (bad) cholesterol from the body. These mice, like people who are born lacking the receptor, are prone to develop plaque buildups in their arteries and are subject to premature and aggressive cardiovascular disease. Unstable plaque (prone to rupture) can break apart causing blood clots to form that block blood flow, which may lead to heart attack or stroke. To mimic fatty plaque development in people, the mice were fed a cholesterol-rich diet for 24 weeks.

Half of the mice were exposed to social stress via sharing their living space with other larger, aggressive mice for short periods of time over ten days. After each stress episode, the mice were evaluated for social avoidance and depression-like or anxiety-like behaviors. The mice that showed the behaviors were classified as susceptible (depressed), and the others were classified as resilient (effective coping). The other half of the mice (controls) were not exposed to social stress.

Both the susceptible (depressed) mice and the control mice were treated with an LDL-lowering medication for three weeks, to mimic cholesterol treatment in humans. Previous studies have found that when LDLr-deficient mice are treated with lipid-lowering medication, arterial plaque becomes less inflammatory and more stable. After treatment, the mice were tested for changes in the number of inflammatory cells in their plaque, the number of inflammatory white blood cells (monocytes) circulating in the blood, and the number of bone marrow cells, which are precursors to the immune cells abundant in plaque. The resilient mice were similarly evaluated, however, the analyses for this group of mice are ongoing.

The analyses found that, compared with mice not exposed to stress (the control group), the susceptible (depressed) mice from the group exposed to social stress had:

- 50% higher rise in immune cells within plaque in their arteries;

- Double the number of circulating monocytes, which are precursors of inflammatory cells;

- 80% increase in the number of immune-cell precursors in bone marrow;

- Less collagen within plaque in the arteries, which is an indicator of instability; and

- A similar lowering of lipid levels when compared to the control groups’ response to LDL lowering medication.

“The major finding is that repeated stress and the physiological and behavioral effects of hostile interactions (social defeat) appear to prevent the full beneficial changes to plaques that should be induced by lipid-lowering medications,” Kireccibasi said.