Eliminating the gene SRC-3 in animal models of breast and prostate cancer triggered a lifelong anti-cancer response, according to work by researchers at Baylor College of Medicine. They eliminated SRC-3 specifically in immune cells called regulatory T cells (Tregs). Not only were those animals protected, but transferring Tregs without SRC-3 to other animals carrying breast cancer tumors also resulted in long-term elimination of tumors without negative side effects.

The paper was published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

SRC-3 is highly expressed in all human cancers and strongly expressed in Tregs, which regulate the immune response to cancer.

“More than 30 years ago, my lab discovered a protein we called steroid receptor coactivator (SRC) that is required for the effective regulation of gene activity,” said corresponding author Bert W. O’Malley, chancellor and professor of molecular and cellular biology at Baylor. “Since then, we have discovered that a family of SRCs (SRC-1, SRC-2 and SR-3), regulates the activity of a variety of cellular functions.”

Intrigued by the abundance of SRC-3 in Tregs and suspecting that it might play a role in controlling cancer progression, O’Malley and his colleagues investigated the effect of eliminating the gene SRC-3 in Tregs on breast cancer growth.

The team generated mice lacking the SRC-3 gene only in Tregs and then compared breast cancer progression in these mice with the progression in mice that had the SRC-3 gene.

“We were surprised by the results,” O’Malley said. “Breast tumors were eradicated in the SRC-3 knock-outs. A subsequent injection of additional cancer cells in these mice did not give rise to new tumors, showing that there was no need to generate additional SRC-3 knock-outs to sustain tumor resistance. Importantly, transferring these cells to animals carrying pre-established breast tumors also resulted in cancer eradication. We obtained similar results with prostate cancer.”

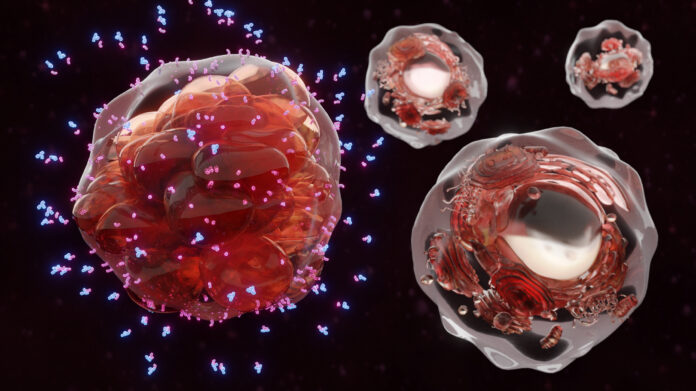

The team also discovered that Tregs lacking SRC-3 mediated long-lasting tumor eradication by effectively modifying the environment surrounding the tumor into one that favored its elimination.

Using a variety of laboratory techniques, O’Malley and his colleagues discovered that the modified Tregs proliferated extensively and preferentially infiltrated breast tumors where they released compounds that generated an anti-tumor immune response. On one side, the compounds facilitated the entrance of immune cells—T cells and natural killer cells—that directly attacked the tumor and, on the other side, modified Tregs blocked other immune cells that attempted to stop the anti-tumor response.

“Other published treatments seem to reduce tumor burden or eliminate the cancer for some time, but in most cases it returns. Our findings in animal models are the first to show that Tregs lacking SRC-3 eradicate established cancer tumors and appear to confer long-lasting protection against recurrence,” said first author Sang Jun Han, associate professor of molecular and cellular biology at Baylor. “

Baylor has licensed all the patents and intellectual property underlying these discoveries to CoRegen.