Researchers at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania have developed a new and improved CAR T cell therapy approach for solid tumors by simultaneously knocking out two inflammatory regulators and boosting T cell expansion.

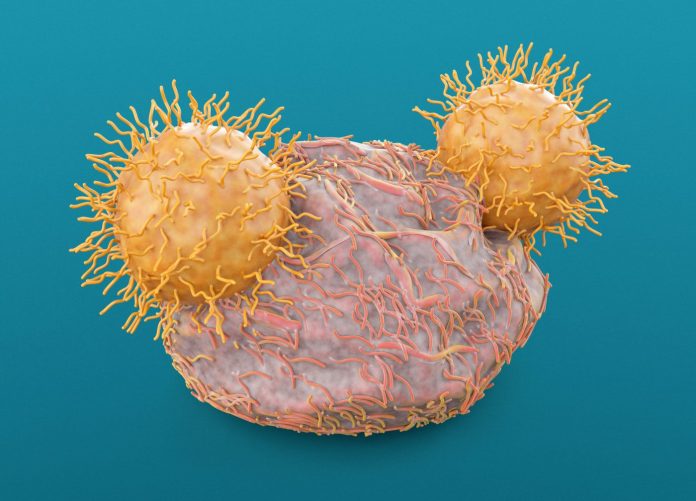

CAR T cells are immune cells taken from an individual patient and genetically engineered to express proteins known as CAR—chimeric antigen receptors—on their surface in order to bind specific proteins on the surface of target cells and eliminate them.

Despite already being approved as treatment for several cancers in the U.S., CAR T cell therapies remain largely ineffective against solid tumors, such as lung cancer and breast cancer. According to researchers, this could be due to T cell exhaustion, where the immune cells are “exhausted” by the constant antigen exposure in the tumor environment and no longer able to generate an immune response.

Reporting in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, researchers at the University of Pennsylvania have now developed a “one-two punch” strategy to help overcome this phenomenon. In a preclinical study, the scientists simultaneously disrupted two regulators that control gene functions related to inflammation: Regnase-1 and Roquin-1, leading to a 10 times greater T cell expansion in models.

The researchers say that, by knocking out the genes, the T cells are able to produce a hyperinflammatory response, allowing them to target cancer cells again and indirectly overcome the effects of T cell exhaustion.

“Each of these two regulatory genes has been implicated in restricting T cell inflammatory responses, but we found that disrupting them together produced much greater anticancer effects than disrupting them individually. By building on previous research, we are starting to get closer to strategies that seem to be promising in the solid tumor context,” said David Mai, bioengineering graduate student at the University of Pennsylvania and lead author of the study.

The genes were disrupted both simultaneously and individually using CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing in healthy donor T cells. After CRISPR editing, the modified T cells were expanded and infused in solid tumor mice models, where researchers observed a 10 times higher T cell expansion when using the double-knockout, resulting in increased antitumor immune activity and longevity of the engineered T cells.

“CRISPR is a useful tool for completely ablating the expression of target genes like Regnase and Roquin, resulting in a clear phenotype, however there are other strategies to consider for translating this work to the clinical setting, such as forms of conditional gene regulation,” said Neil Sheppard, PhD, head of the CCI T Cell Engineering Lab and co-co-author of the study.

“We’re certainly impressed by the antitumor potency that was unleashed by knocking out these two non-redundant proteins in combination. In solid tumor studies, we often see limited expansion of CAR T cells, but if we’re able to make each T cell more potent, and replicate them to greater quantities, we expect T cell therapies to have a better shot at attacking solid tumors,” Sheppard concluded.