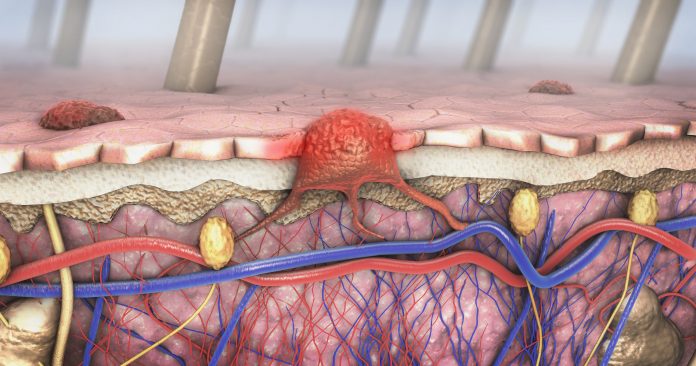

New research from the Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center shows that age-related changes in the skin that make it less elastic increase the release of a protein that may help foster melanoma metastases. The protein, ICAM1 helps stimulate blood vessel growth in a tumor and also makes blood vessel more “leaky,” allowing tumor cells to escape from the bloodstream and spread through the body.

The research was published this week in the journal Nature Aging.

“As we age, the stiffness of our skin changes,” explains Ashani Weeraratna, PhD, associate director for laboratory research at the Kimmel Cancer Center and professor of oncology at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. “That not only has physical implications, but it also has signaling implications and can lead to increases in new blood vessel growth or disruption of blood vessel function.”

Weeraratna’s lab at Johns Hopkins has focused on how changes related to aging aid in the spread of melanoma and also make it more resistant to current therapies. Older patients are known to be more likely to develop melanoma and die from it than are younger patients, and experience more disease recurrence.

In previous research, Weeraratna and colleagues identified a different protein, HAPLN1, that helps to maintain the structure of the extracellular matrix, a network of molecules and minerals that helps keep the skin supple. But as people age, less HAPLN1 is released which causes the skin to become stiffer.

In the new research, the investigators show that the reduction of HAPLN1 indirectly increases ICAM1 levels by causing the stiffening of the skin, which changes cellular signaling. These changes promote angiogenesis, the growth of blood vessels that feed tumor growth while also allowing cancer cells to leak out of blood vessels throughout the body fostering cancer’s spread.

Using this knowledge, the Hopkins investigators treated older mouse models with melanoma with drugs that block ICAM1 and showed that this both shrunk existing tumors and reduced metastasis. Ongoing studies in the Weeraratna lab are now focused on finding more precise ways of targeting ICAM1 with new drugs with the potential of developing targeted therapies for older people with melanoma.

Further, the researchers believe their findings might also be beneficial in discovering new approaches to treating other cancers related to aging. They note the previous approaches to target growth factors that foster angiogenesis have not proven effective in many tumor types, so targeting ICAM1 is a promising new approach.

“We know that age-related angiogenesis is important in many different cancers and multiple aspects of health and disease,” said Weeraratna. “Finding a new way to target that in different tumor types could have a big impact.”

Since angiogenesis is also important in wound healing not just of the skin, but also in the cardiovascular system and the brain, a better understanding of ICAM1’s role in these activities could also have important implications in treatments for these conditions in older adults.