A study involving 381 children has linked cognitive function with the enrichment or depletion of certain species of gut microbes. The findings are among the first to directly investigate associations between early brain development and specific gut bacteria, say lead author Kevin Bonham, of the Department of Biological Sciences at Wellesley College. and colleagues. Their findings, they say, pave the way for developing biomarkers for neurocognition and brain development.

Using a combination of statistical and machine learning models, the team showed that species including Alistipes obesi, Blautia wexlerae, and Ruminococcus gnavus were enriched or depleted in children with higher cognitive function scores. They studied children between the ages of 18 months and 10 years.

The link between the brain and the gut microbiome, commonly referred to as the microbiome-gut-brain axis, is a keen area of recent research. For example, studies involving humans and animals have found that gut microbes are associated with the development of neurological disorders such as autism spectrum disorder, Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and depression.

Despite wide-ranging evidence that healthy children undergo remarkable brain development in their early years, and that gut microbial diversity soars after the transition to solid food, few studies have examined how these two processes are interconnected.

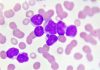

Bonham et al. evaluated microbial communities in stool samples taken from 381 healthy children between the ages of 40 days and 10 years old, each within a week of various age-appropriate cognitive assessments.

Using shotgun metagenome sequencing the researchers found that older children hosted more diverse gut microbial communities, and by 18 months old, variations in microbial species and microbes’ metabolism of short-chain fatty acids were both significantly associated with cognitive function scores.

For example, the enrichment of species such as Alistipes obesi, as well as the enrichment of short-chain fatty acid-producing species Eubacterium eligens, and Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, were associated with higher cognitive function in children over 18 months old.

“Although we did not directly test the causal relationships between gut microbial taxa and their genes, the gut, and the brain, this study provides clear and statistically significant associations that could serve as targets for future efforts in preclinical models,” the authors write.

The authors say this research is the first to examine the gut-brain-microbiome axis in normal neurocognitive development among healthy children. The integration of multivariable linear and machine learning models to analyze the complex relationship between gut microbiome profiles and neurodevelopment is innovative. These models not only established the association of gut microbiota with cognitive function but also predicted future cognitive performance based on early-life microbial profiles.

This research, the authors say, could lead to early detection of developmental issues and interventions, potentially mitigating long-term cognitive challenges. It highlights the importance of gut health in early childhood, suggesting dietary and lifestyle considerations for parents and healthcare providers. Furthermore, they say, this study marks a first step in formulating hypotheses that can be tested experimentally and in animal models.