A team of researchers at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania has identified a new therapeutic target and biomarker indicative of kidney disease. Their research, published in Nature Metabolism, found that metabolic changes to an enzyme “helper molecule” nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD) helped map changes in both health and diseased mouse and human kidneys.

The investigators report that in diseased kidneys they consistently saw a prominent decrease in the presence of NAD compared with healthy kidneys. When the mice were provided with an over-the-counter supplement, it proved effective in reversing NAD loss showing that the enzyme could play an important role in protecting the kidney.

“We hope that this research can lead to improved care in the future. So when patients have metabolite changes, they can receive treatment before kidney disorders arise,” said co-lead investigator Katalin Susztak, MD, PhD, a professor of Nephrology and member of the Institute for Diabetes, Obesity, and Metabolism (IDOM) and Kidney Innovation Center at Penn Medicine.

The need for new and more effective treatments for kidney disease is pressing. According to the National Kidney Foundation, approximately one million people die from untreated kidney failure worldwide each year. Despite the prevalence of the disease there have been few new treatments or treatment approaches developed over the past 40 years.

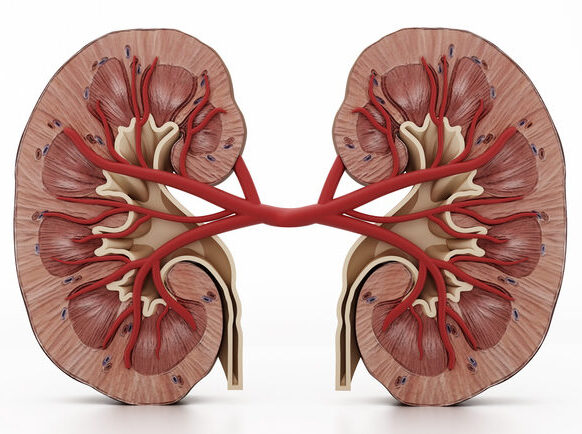

Susztak and her colleagues are trying to change this with their approach. Prior to their recent work, human patient samples had not been used in metabolomic studies to understand the role of small molecules in kidney disease. The team leveraged unbiased metabolomic studies to identify the changes of NAD in both human and mouse kidneys. The application of the supplements either nicotinamide riboside or nicotinamide mononucleotide boosted NAD and protected the kidney function of the mice by protecting the mitochondria of kidney tubule cells.

Kidney tubule cells’ role is to filter and return critical nutrients to a person’s bloodstream. But when the mitochondria in those cells is damaged, it can lead to inflammation which in turn activates the development of kidney disease. The NAD supplements given to the mice helped keep the inflammation in check and as a result halted the progression of kidney injury.

“Identifying these downstream mechanisms that are sensitive to NAD is critical to understanding which conditions may benefit from NAD supplementation,” said co-lead investigator Joseph Baur, PhD, a professor of Physiology at Penn and member of the IDOM.

The new research should provide a basis for additional studies of the role changes in metabolite levels play in the development of kidney dysfunction and injury. Further, understanding the activity of these metabolite will serve as targets for the development of novel approaches to treat kidney disease.