New research published in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute shows that women treated for breast cancer exhibit faster biological aging than those who remain breast cancer free.

“Breast cancer survivors have higher rates of various age-related diseases, such as cardiovascular disease, and experience faster physical and cognitive decline than women without a history of breast cancer. In this study, we wanted to explore the biology behind this and examine whether certain cancer therapies had a greater long-term impact on survivors,” said lead study author Jacob Kresovich, Ph.D., MPH, assistant member of the Cancer Epidemiology Department at Moffitt Cancer Center.

Of women who are diagnosed with breast cancer the association with faster biological aging was more common in those who had received radiation therapy. Women who had undergone surgery showed no association with increased biological aging suggesting that contracting cancer in not the factor that increases the aging effect.

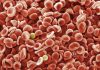

Biological age is a reflection of a person’s cellular and tissue health and is a different measure than chronological age. For this study, the researchers used data from the Sister Study which is led by NIEHS, a part of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). This research is looking to identify the environmental factors that affect breast cancer risk and risk of developing other diseases. More than 50,000 women aged 34 to 74 who had a sister diagnosed with cancer but had not been diagnosed themselves enrolled in the study between 2003 and 2009. All participants are contacted yearly to provide health status updates and participants provided a blood sample at the time of enrollment. A sample of participants were also asked to provide a second blood sample between five and 10 years after enrollment.

The investigators studied a subset of women who had provided both bloods samples, and of the 417 women in that subset, 190 had been diagnosed and treatment for cancer between the two blood draws. To determine biological ages of participants, the researchers analyzed all the blood samples using three established epigenetic metrics of biological aging: PhenoAgeAccel, GrimAgeAccel and DunedinPACE. Each metric examine DNA methylation to determine specific epigenetic changes that can determine a person’s risk of developing age-related disease and biological aging.

While the results determined that women treated for breast cancer between the blood draws exhibited faster biological aging to those who had not developed cancer, there were notable differences in the rate of change based on the treatments they received.

“We looked at three types of treatments used for breast cancer: endocrine therapy, chemotherapy and radiation therapy. We found a strong association between faster biological aging and those who received radiation therapy,” Kresovich said.

The research did not, however, find the reason why radiation treatment led to faster biological aging and the results don’t necessarily suggest women should not avoid this form of treatment.

“Radiation is a valuable treatment option for breast cancer, and we don’t yet know why it was most strongly associated with biological age,” said Dale Sandler, Ph.D., chief of the NIEHS Epidemiology Branch and a co-author on the paper. “This finding supports efforts to minimize radiation exposures when possible and to find ways to mitigate adverse health effects among the approximately 4 million breast cancer survivors living in the United States.”