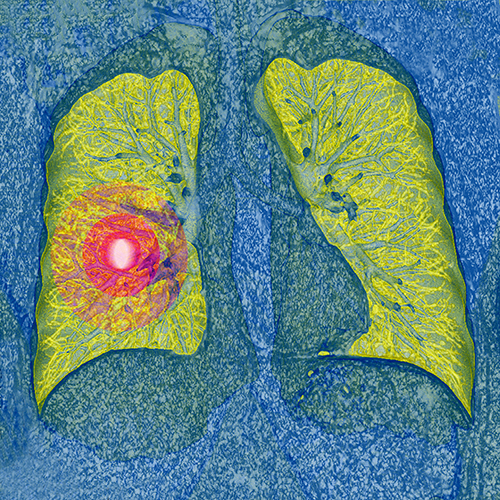

Current clinical guidelines call for annual lung cancer screening of patients 50 years and older with a history of smoking using low-dose computed tomography. Previous results from the National Lung Screening Trial (NLST) have shown that this screening increases early detection and reduces mortality. However, a new study published in the Annals of Internal Medicine suggests lung cancer screening is riskier for patients in routine clinical practice compared to those who took part in the NLST.

“We found that adults in our study had much higher rates of downstream imaging, procedures, and complications in comparison to those rates observed in NLST,” said Katherine Rendle, Ph.D., first author of the study and an assistant professor at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. She conducted the study in collaboration with researchers across the Population-based Research to Optimize the Screening Process (PROSPR) network.

According to Rendle and her colleagues, the study highlights the need for quality measures and other strategies to ensure the benefits of screening are maximized and the potential harms are mitigated. “As real-world evidence related to lung cancer screening continues to grow, guidelines should incorporate these outcomes and change as needed,” Rendle said.

For the current study, the research team set out to identify rates of downstream procedures and complications associated with lung cancer screening. Downstream procedures included additional imaging scans, biopsies, and thoracic surgery. They gathered healthcare data from electronic health records for 9,266 people screened for lung cancer across five U.S. healthcare systems between 2014 and 2018. They found 16 percent of all patients had a baseline screening showing abnormalities. Of those patients presenting abnormalities, 10 percent were diagnosed with lung cancer within 12 months. Of all patients, 32 percent underwent downstream imaging and 3 percent underwent downstream procedures.

The team also found that, in patients undergoing invasive procedures after abnormal findings, complication rates were substantially higher than those in NLST; 31 percent vs. 18 percent for any complications, and 21 percent vs. 9 percent for major complications.

According to Rendle, results from clinical trials are often different than those observed in real-world settings. Clinical trials often have restrictive inclusion criteria of those eligible for trials and standardize diagnostic management during trials. “This is certainly the case for lung cancer screening, where patients being screened in real-world settings tend to be older and have more comorbid conditions than those patients in NLST,” she said. Diagnostic management also differs in practice, Rendle explained.

Still, the magnitude of the results were a surprise to the researchers. “Given the relative newness and challenges with implementing lung cancer screening, our results are not entirely unexpected,” Rendle said. She also said the current results indicate that those being screened may be receiving more aggressive diagnostic management after screening than is necessary.

Rendle and her colleagues are conducting ongoing studies, breaking down potential harms of lung cancer screening by race, sex, and comorbid conditions. They also have several studies looking at how to improve outcomes in lung cancer screening. These projects include ongoing work developing diagnostic quality measures related to lung cancer screening and large pragmatic trials designed to increase quality and equity of shared decision making for lung cancer screening.

“Given known differences between trials and real-world practice, it is essential that we continue to monitor both benefits and risks in real-world practice,” she said.